“Unexpected” Consequences: Expert Discusses Impact of Lockout Tagout Standard Changes

The decision on July 18, 1996 by a federal appeals judge to vacate three citations against General Motors reverberates anew as interested parties await the fate of one word—unexpected—in a long-established standard.

Almost 21 years ago, Secretary of Labor Robert Reich, on behalf of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), argued that the citations brought against GM’s former Delco Chassis Division should stand on the basis of “unexpected energization or start up” of machines. The citations, issued under OSHA’s 29 CFR Section 1910.147 lockout/tagout (LOTO) safety standard, were given to GM when over the course of multiple visits OSHA inspectors saw workers service three machines that remained connected to power during the maintenance.

The judge disagreed, noting in his opinion that the equipment in question, which featured interlocked gates that deactivated the machine when opened, among other safety features, could not have started up without adequate warning for the employees.

OSHA’s response to the decision was swift and over the intervening years has proven quite impactful. “GM won that case so what OSHA did after that point was it upped its ability to bring out other reasons why the warning system by itself was not considered sufficient,” explains Todd Grover. “So, they haven’t lost a case since, to my knowledge.”

Grover is the global senior manager-applied safety solutions at The Master Lock Company and he is a member of ANSI/ASSE Z244 Accredited Standards Committee. Plastics Technology caught up with him after he presented on the newly released ASSE/ANSI Z244.1 LOTO standard, and OSHA’s renewed interest in LOTO.

“OSHA came back and said, ‘We want to upgrade standards to benefit all,’ and they wanted to change one word in the lockout standard and the ANSI committee pushed back and said, ‘Wait a minute, don’t just change one word; think about what you’re asking people to do?’” Grover said. “Maybe that argument will go places. I know we would like it to, and we’re going to promote that.”

First published in 1982, Z244.1—as all are ANSI standards—is voluntary. But as is often the case, the standards can become the basis for OSHA regulations, which are, of course, mandatory. That 1982 standard was studied by OSHA and “enhanced”, according to Grover, and it became the basis for OSHA’s 29 CFR 1910.147 standard, which was issued in September 1989.

ANSI ratified and re-released related standards in 2008 and 2014, with no real changes, Grover said, but in 2016, ANSI issued a “decidedly large rewrite” after starting work on revisions in 2014. The updated standard tried to take into account advances made in machine control and safety. “Back in 1989, interlock protection was nowhere near as robust as today,” Grover said, noting that today’s machine guarding is highly reliable.

Given that, and the potential impact of having to completely power down an injection molding machine during a mold change, for instance, much of Grover’s presentation touched on so-called “alternative methods.”

These apply to situations where lockout is not an option, and, in his Safety presentation, Grover listed some instances when they could apply:

- Energy required to do the job

- Not feasible/practical

- Documented risk assessment

- Show task can be performed with acceptable risk level

- Inherent hazards can’t be controlled using lockout or tag out

- Energy required to keep machine in safe state

- Repetitive cycling of energy isolation device compromises its function

Grover said before an alternative method to lockout is considered, workers should ask these questions:

- Is energy required to perform tasks

- Does full isolation lockout limit ability to do task

- Are there modifications to the task or equipment that would overcome current limitations

- Are there options to reduce number of energy sources; can a partial lockout be managed

“It’s obviously a big challenge to lock out the machine during mold changes because you need the mechanical movement of the machine to get the molds in and out,” Grover said. “It’s an important aspect, so there, I think, alternative procedures have a whole lot of value because you’re able to discuss what’s actually going on. Where are the risk points; what can we do to manage the exposures and document the right way to do this job in a manner that’s equivalent to lockout in terms of nobody having an opportunity to get hurt.”

Related Content

How to Select the Right Tool Steel for Mold Cavities

With cavity steel or alloy selection there are many variables that can dictate the best option.

Read MoreHow to Optimize Pack & Hold Times for Hot-Runner & Valve-Gated Molds

Applying a scientific method to what is typically a trial-and-error process. Part 2 of 2.

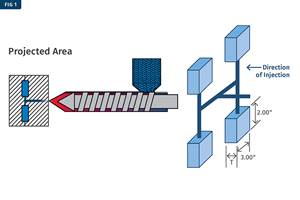

Read MoreIs There a More Accurate Means to Calculate Tonnage?

Molders have long used the projected area of the parts and runner to guesstimate how much tonnage is required to mold a part without flash, but there’s a more precise methodology.

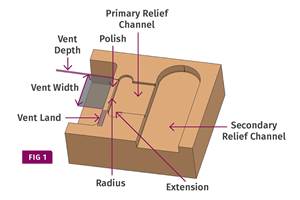

Read MoreBack to Basics on Mold Venting (Part 2: Shape, Dimensions, Details)

Here’s how to get the most out of your stationary mold vents.

Read MoreRead Next

11th Hour Extension to Proposed Lockout/Tagout Rule Changes

Deadline extended from Jan. 1 to Jan. 4, 2017 as stakeholders weigh the potential impact on injection machine maintenance and mold changes.

Read MoreBeyond Prototypes: 8 Ways the Plastics Industry Is Using 3D Printing

Plastics processors are finding applications for 3D printing around the plant and across the supply chain. Here are 8 examples to look for at NPE2024.

Read MoreMaking the Circular Economy a Reality

Driven by brand owner demands and new worldwide legislation, the entire supply chain is working toward the shift to circularity, with some evidence the circular economy has already begun.

Read More