Global Competition - Injection Molders' Weapons: Advanced Technology or Secure Market Niche

Growing competition from low-cost overseas producers has spurred U.S. injection molders to reconsider what market segments they serve and how.

Growing competition from low-cost overseas producers has spurred U.S. injection molders to reconsider what market segments they serve and how. Domestic molders involved in consumer products, electronics, medical, and automotive applications are fighting the allure of lower labor costs abroad, which have captured the interest of their OEM customers. This labor-cost advantage abroad is a persistent threat despite foreign producers’ disadvantages of longer time to market, higher transport and inventory costs, quality and regulatory-compliance concerns, and longer response times.

At present, foreign competition from regions of lower labor cost is most acute for molded parts of simple design, whether produced in low or high volume. Yet the impact of newly emerging foreign competition in Asia and Latin America has been so profound that molders of all types of parts are defining new strategies to meet current or possible future challenges.

One large U.S.-based molder, United Plastics Group (UPG) in Oak Brook, Ill., thinks it has a pretty good idea of what kinds of jobs are better suited to U.S. or to overseas production. UPG should know, since it has 10 plants in the U.S., Mexico, U.K., and China. Matt Langton, v.p. of sales and marketing, says two kinds of applications belong in low-cost countries:

- Labor-intensive jobs and ones not worth automating because of frequent model turnover.

- Small products rather than bulky ones that are expensive to ship over long distances.

Langton says the products likely to stay in the U.S. are ones that involve special quality or regulatory standards, proprietary intellectual capital (patents), or potential for advanced automation. He notes that medical products are a good example of all three. However, experienced U.S. medical molders are starting to move to the Far East and taking their know-how with them.

Langton adds that automation in domestic plants is an effective counterbalance to low labor costs abroad. What’s more, low-cost labor can be offset by both shipping costs and additional inventory expenses. “You have seven weeks on the boat from China, so you must keep more inventory at both ends of the chain.”

Molders have applied a diverse range of strategies to stay competitive. Some have abandoned what had been their core markets and established a presence in new areas. Some have followed major customers overseas, establishing their own plants there or forming joint-ventures or alliances with local molders. Other domestic firms are being proactive–setting up in Mexico or overseas to offer lower-cost manufacturing to OEMs here. Still others have turned their focus inward, developing proprietary in-house molding capabilities with sophisticated molding technologies and secondary operations to add value that can’t yet be matched by foreign producers. U.S. processors overall agree on one thing: Molders must specialize.

A change of direction

Mack Molding, a custom molder and contract manufacturer headquartered in Arlington, Vt., saw its core business vanish overseas a few years ago. “We were a leading manufacturer of computer components for Hewlett-Packard, Xerox, and others in the late 1980s and early ’90s,” says Jeff Somple, president of Mack’s Northern Div. “Then, in 2000, we felt the competitive pressure from molders in lower-cost regions like China. Our three biggest customers decided to source the components elsewhere, and the business model we had built was gone.

“We had the option to go to China and build a plant, but we had no desire to be an offshore manufacturer,” Somple says. So Mack held a strategic meeting and formed a new business model based on what technologies it had, what it did well, and what the foreign competitors didn’t do as well. “We had a strong supply network, we had large-tonnage machines and a highly skilled workforce with expertise in plastics and metal. Then we focused on completely new markets for us, markets with barriers to entry by foreign producers due to regulatory concerns or production expertise.”

Mack targeted two widely separated fields: medical molding, which made up less than 1% of its business at the time, and molding very large “mega-parts” with highly cosmetic surfaces. “We hired engineers with an aptitude for medical molding. We beefed up our expertise in laser welding and laser engraving. We acquired smaller presses for overmolding, and we integrated assembly operations as well,” says Somple.

Medical molding now comprises about 35% of Mack’s product mix and that share is growing. Mack competes with some big contract manufacturers partly by pursuing medical jobs with smaller volumes than the others are interested in. Even at low volumes, these are multi-million-dollar projects.

Meanwhile, Mack’s Southern Div. is responsible for super-large-part molding, another new area in which Mack has gained valuable expertise. That division formerly produced TV cabinets but saw the auto market moving away from Detroit and sought to attract it to the Southeast with capital investments in machinery and a $1-million paint line. Mack also developed special skills to mold large parts such as a golf-cart roof in a single shot and to make large structural parts with cosmetic finishes.

“Now we are much smarter about the projects we take. For example, we ask why the customer doesn’t want to mold the part in a low-cost area,” says Somple. Mack doesn’t want to do all the product development and debugging and then see the job shipped elsewhere for production. It looks for a customer that needs close contact between design and manufacturing to execute quick product changes.

Strength in technology

Another domestic molder that has relied on in-house expertise to insulate itself from foreign competition is Bemis Manufacturing Co., Sheboygan Falls, Wis. Says Steven Kloste, director of market and business development, “We have been feeling the pressure of low-cost goods from Mexico and the Far East, and it is our strategy to stay ahead of it.”

Bemis produces mid- and large-sized cosmetic exterior parts for heavy trucks, cars, recreational vehicles, appliances, boats, agriculture, and lawn equipment from its two U.S. plants. “We are experienced in producing these parts with multi-material coinjection or overmolding or difficult-to-process engineering resins.” Bemis has developed a number of proprietary process technologies that allow it to mold parts with unique characteristics. “That is how we combat overseas competition,” Kloste states.

Bemis has 28 multi-barrel injection machines ranging from 500 to the industry’s biggest press at 6600 tons. Multi-component molding constitutes about 75% of its business, and Bemis has come up with several novel twists on the technology. For example, Bemis coinjected a steering wheel with a PP foam core and fiberglass/PP skin. After the first shot, the tool rotates so that a third barrel can overmold part of the wheel with a soft-touch TPE. Coinjected melt streams can be directed into separate cavities of a family mold. “We are also trying new ways to mold parts to eliminate painting or get the part weight down,” Kloste adds.

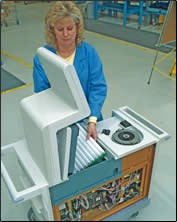

Also seeking to protect itself from competition with in-house technical resources is The Tech Group in Scottsdale, Ariz., a division of West Pharmaceutical Services. This major global contract manufacturer in healthcare and consumer markets is not seeing much foreign competition in the markets it serves, due largely to its strengths in molding with assembly, says v.p. Tom Podesta. “About 95% of the projects we undertake feature both molding and assembly. Not many molders in Asia can do both. We positioned ourselves in an area where there is little global competition. We pursue technically challenging applications that feature automation and integrated manufacturing cells. We are also increasing our knowledge of cavity-pressure monitoring and secondary operations such as ultrasonic welding, bonding, laser marking, and printing.”

The company operates more than 400 presses from 17 to 500 tons at 14 plants in the Americas, including one in Mexico, and a single European plant. Podesta says its parent company (whose core business is rubber components) plans to establish a manufacturing site in Asia next year, and Tech Group will likely set up operations there.

Control of part quality

“Three technologies in particular allow us to gain an advantage over foreign outsourcing of molded components, largely because we are better able to control the quality of the part,” says Herb Duggan, molding manager the Automotive Electronic Controls Div. of Methode Electronics, Chicago. This Tier One and Tier Two supplier of automotive electromechanical components and subsystems performs most of its molding (almost entirely with engineering resins) at its Carthage, Ill., plant, although it is establishing a site in China to service General Motors and has facilities in Singapore, Japan, Mexico, and Europe.

One key technology is the eDart cavity-pressure monitoring system from RJG Inc., Traverse City, Mich., which Methode uses to detect part variation before the part leaves the tool. Process monitoring ensures a steady and repeatable molding cycle and automatically separates suspect parts. The process monitoring system eliminates a lot of labor used for part sorting, Duggan notes.

Another part of Methode’s process-improvement efforts is to convert entirely to all-electric presses (from Milacron Fanuc) for process repeatability. The company is also implementing a KanBan lean manufacturing card system to drive its production schedule and keep inventory levels to five days or less. “Competitiveness also comes down to cost,” says Duggan. “We have learned how to produce more without adding labor. Three years ago we would have needed six more people to run at the same throughput as we do today.”

Taking technology abroad

“Medical and some consumer products are in the early stages of moving into lower-cost regions, and the competitive pressure from those regions is increasing,” says Richard Harris, CEO of UPG, a full-service contract manufacturer for medical, consumer, automotive, and electronics OEMs. UPG’s strategy is to hold onto existing customers and attract new ones by providing high-quality, high-volume precision molding capability in several low-cost regions of the world. The company operates 460 molding machines worldwide in 11 facilities, including five in the U.S. UPG will offer large-part molding to Fortune 100 automotive and consumer-product companies from two Mexican plants and will install a Class 100,000 clean room at a new facility in northern Baja California.

In China, UPG established two wholly owned facilities, each with a Class 100,000 clean room. They are ISO certified and FDA registered. “We think that as the medical OEMs start to trust the quality and capacity in a low-cost region like Mexico and China, they will buy more product and launch new products too. We want to be ahead of that curve to help the customers when they are ready to make it happen,” says Harris.

UPG is outfitting its Chinese facilities with the latest Toshiba all-electric presses and it is bringing over there some of its most advanced processes, including two-shot molding, micromolding, clean-room molding, precision gear molding, and assembly.

Advanced technology, flexibility, and broad scope are competitive strategies of Nypro Inc., Clinton, Mass. One of the world’s largest custom molders, it has 40 plants in 17 countries. “Not a lot of companies can handle large-volume product launches featuring massive tool builds, tight-tolerance molding, automation, parts decoration, assembly, or other value-added services globally,” says Steve Glorioso, corporate v.p. for healthcare markets. Nypro also maintains a company standard of no more than 3 ppm part defects (Cpk of 2), which it believes is hard to match by molders in lower-cost regions.

Nypro’s philosophy is that speed to market drives competitiveness. Its plants are configured to provide a range of value-added services, which can be different from plant to plant. “We can produce and paint over one million cell- phone parts a day, with a short turn-around time from the order. We have all or our plants operate in a connected and integrated way,” says Glorioso. Nypro can move technologies such as in-mold labeling, MuCell microcellular molding, and painting from plant to plant. These techniques are gaining popularity in lower-cost regions abroad.

Nypro also developed a new modular, flexible tooling concept called Maxis. It facilitates cost savings through lean manufacturing and uses much less steel than normal molds.

Related Content

Completely Connected Molding

NPE2024: Medical, inmold labeling, core-back molding and Industry 4.0 technologies on display at Shibaura’s booth.

Read MoreCoinjection Technology Showcases Recycled Material Containment

At Fakuma, an all-electric PXZ Multinject machine sandwiches a black core made of mechanically recycled PC/ABS within an outer layer made of chemically recycled ABS.

Read MoreArburg Open House Emphasizes Turnkey Capabilities

Held at the company’s U.S. headquarters in Rocky Hill, Connecticut, the event featured seven exhibits, including systems that were designed, sourced and built in the U.S.

Read MoreCompact Solution for Two-Component Molding

Zahoransky’s new internal mold handling technology foregoes the time, space and money required for core-back, rotary table or index plate technologies for 2K molding.

Read MoreRead Next

See Recyclers Close the Loop on Trade Show Production Scrap at NPE2024

A collaboration between show organizer PLASTICS, recycler CPR and size reduction experts WEIMA and Conair recovered and recycled all production scrap at NPE2024.

Read MoreFor PLASTICS' CEO Seaholm, NPE to Shine Light on Sustainability Successes

With advocacy, communication and sustainability as three main pillars, Seaholm leads a trade association to NPE that ‘is more active today than we have ever been.’

Read More