Southwestern Missouri is a rolling plateau draped with a patchwork of cattle farms, streams and forests. The diverse landscape makes a pleasant drive, and just 20 miles short of the Kansas border you’ll find the small town of Lamar, birthplace of Harry Truman. Recently, it also became the birthplace of Capital Polymers.

In 2013, a recycling plant and wood mill in Lamar began supplying materials for composite decking. Seven years later, the plant had entered decline. Rubbish piled up inside, equipment maintenance had been neglected, and financial problems led investors to foreclose. Without a dramatic change in direction, the facility would be shut down and the town of Lamar (population 4266) would lose an important source of employment.

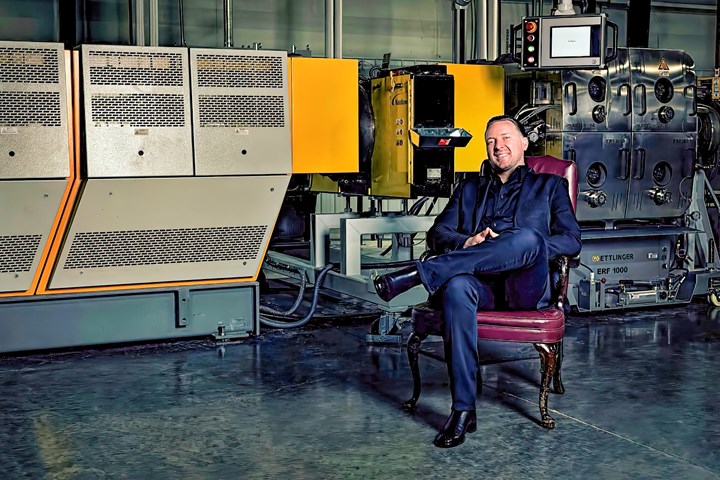

Investors sought a leader with a track record of starting up new plants, to form a new company and renew the facility. They found Mark Merritt, and Capital Polymers was born.

Merritt had five days to decide to shoulder the effort, but the plant was only four hours’ drive from his home in West Des Moines, Iowa. After a brief visit to survey the situation, he decided to give it a shot.

A New Life for a Recycling Plant

It was immediately obvious that there were too many safety hazards to keep running. The first thing the new company did was shut production down and launch a cleanup effort. A bulletin board on the wall at Capital provides some “before” photos: scrap material littering the floor, bags of rubbish in disordered heaps. Stray cats and raccoons made their homes indoors. The facility had been processing a lot of agricultural waste, including scrap from poultry companies. The stench was stomach-churning. Cleanup kept 15 dump trucks busy for a month and cost over a million dollars.

“When you have bad equipment, you don’t really know how bad until you’re running it.”

Soon after resuming operations, it became apparent that the facility needed more than a thorough cleaning. “When you have bad equipment, you don’t really know how bad until you’re running it,” says Merritt. In the fall of 2021, the main extruder caught fire, causing $3.5 million worth of damage.

To stay in the market and keep its workforce engaged, Capital continued to process material on its grinding line while working with suppliers to procure replacement equipment. In such a small town, every job counts. “I’ve never come into a plant and fired everyone to start from scratch. That’s not right,” Merritt notes.

Bags of recycled LDPE in storage converted from the former production area. At far left, bins of used toys from Goodwill await recycling. (Photo: Matt Stonecash)

Today, it is a facility transformed. The only quadruped in sight is Xavier, Merritt’s amiable Doberman, who dashes playfully about, paws sliding on the polished concrete. Material sits in neat orthogonal rows of labeled bags and bins. And the material is various. Retail film bags are present, as one would expect given the plant’s history of processing film for composite lumber, but also discarded trash cans, car parts, hydropulp (paper mill scrap), diapers, pallets, toys, and carpet.

Discarded trash bins await shredding and reprocessing. (Photo: Matt Stonecash)

The plant has been completely rearranged; the former production area is now given to storage, with the former storage areas populated with five lines for shredding, grinding, washing, extruding and pelletizing. There are also offices on-site for quality assurance and logistics. Capital relies on contract work as little as possible, preferring to invest in its own permanent staff.

According to Merritt, reconfiguring a facility so extensively can be more challenging even than starting from scratch. Beyond the cleanup and equipment replacement, utilities had to be rerouted and structural reinforcement added. Now, however, Capital has a facility to suit its needs and then some, with space to grow in its 280,000 ft2.

Recycling-as-Service: Shifting to Toll Processing

Even in the short history of Capital Polymers, the recycled plastics industry has seen significant change. Legislation and brand initiatives have ensured that demand is high, but downward pressure on prices has been a challenge. At time of writing, pellets from reclaimed LDPE film are priced around 38ȼ/lb, according to the most recent OPIS report.

Capital is adapting to the challenge in two ways: making better use of more difficult (therefore cheaper) materials and adopting a toll processing business model. “We have to innovate,” says Merritt. “We have to run stuff that no one else will.”

Whereas a more traditional recycling model would involve buying scrap, recycling it, then selling it to a manufacturer, a toll processor is contracted to process an amount of material that it then returns to its owner. Capital’s predecessor was heavily involved in recycling agricultural film, along with wood scrap, and selling to composite decking manufacturers. Today Capital has diversified the materials it processes and shifted its business model to a focus on toll processing.

“We have to innovate. We have to run stuff that no one else will.”

Companies that lack the financial resources to invest in their own equipment, or are dissuaded from doing so by the price trends in recycled resins, can turn to a toll processor. This allows them to get into the recycling game while bypassing the upfront cost of equipment.

“It can be tough, because one day you think you’re running one material, and suddenly you have to switch over to something else. But that’s tolling,” notes Merritt.

Capital’s Weima shredder breaks down discarded plastic pallets. (Photo: Matt Stonecash)

Some of the recycled plastic material is still processed into other plastic products, while a majority becomes feed for pyrolysis. Without the mechanical recycling steps performed by Capital, pyrolysis can turn improperly prepped material into an unusable char, negatively impacting output.

The plant capacity is currently 53 million lb/yr. Capital expects additional investments to expand this capacity to 100 million lb/yr in the second quarter of 2023.

Ready to Tackle What Others Won’t

With the new equipment up and running, Capital seems ready for whatever its customers want to throw at it, be it PP, HDPE, LDPE or LLDPE. The centerpiece is a custom-built C:Gran extruder from NGR, with upgraded gearbox and hardened screw, used in conjunction with an Ettlinger (Maag Group) ERF 1000 melt filter. “Not only does Ettlinger make the finest melt-filtration equipment, they really are great to work with,” says Merritt.

Capital’s primary extrusion line, with NGR C:GRAN extruder and Ettlinger ERF 1000 melt filter.

(Photo: Matt Stonecash)

Another key to Capital’s operation is its washing line from Herbold Meckesheim, which allows it to process some of the toughest post-industrial scrap, containing up to 30% paper. By filtering out contaminants as small as 400 microns, the plastic becomes a usable product.

Capital’s latest venture is a new trial recycling plastic from medical biowaste “sharps” containers. It’s expected to be the most difficult material yet. Not only does it present a unique handling challenge, but metal contamination may be a problem. Based on specific gravity, the stainless steel and rubber plungers should separate from the plastic in the float tank. But that’s theory, and Capital will soon know what happens on a commercial scale.

“You can run stuff on a bench all day long, but until you run 50 million lb of the stuff you don’t really know,” explains Merritt. The output would not be suitable for a return to medical-grade plastics but could potentially be used in products like composite decking or agricultural pipe. We want people to know we will try anything.”

A large container of medical waste awaits a recycling trial at Capital Polymers. (Photo: Matt Stonecash)

Capital wants to upgrade its material handling as well, so the process flow can be customized based on the material being processed. A system of diverter valves would send materials to the right plant. For example, clean, post-industrial scrap may not need to go through the washing line, so it would be diverted around that process, conserving time, energy and water.

Investing in flexibility makes sense for a business that prides itself on being able to tackle anything. “We have some idea, but we don’t really know what is on the truck until it gets here,” said Merritt.

Whatever the future may bring, Merritt is confident in his operators.

“Our operators are the best in the world,” said Merritt. “Because they’re accustomed to so many different things, they don’t get scared off by anything. We know how to work with the temperatures and slow the machine down or speed it up, change the blade to a different micron size. It’s the hard stuff that no one else wants to process that makes us pretty unique.”

A Steward of the Land

For many challenging materials, a flexible, adaptable processor like Capital Polymers may be the last, best option standing between plastics and landfills. For Merritt, whose family has been farming in Nebraska and Iowa for five generations, recycling is part of being a good steward of the land.

“It isn’t only landfills – sooner or later stuff will be leaking into places that are really undesirable, like into our drinking water,” said Merritt. “We are practicing what we preach and that is, ‘Keep it out of the landfill as much as possible.’ And if it’s hard, and nobody else wants to run it, send it to Capital, we’ll give it a shot.”

Related Content

Generation Gap? Not at Packaging Personified

Started at a kitchen table and now in its third-generation of family involvement, this vertically integrated supplier of flexible packaging traces its success to closely aligning with customers and continually investing in new technology across its films, printing and converting operations.

Read MoreInjection Molder Bases Company Culture on Employee Empowerment

After more than two decades in the industry, Rodney Davenport was given the opportunity to create an injection molding operation in his own vision, and — in keeping with the product he was making — to do so from the ground up.

Read MoreBack in the Family Business

In its 45th year, Precision Molded Plastics has carved out a technology and market niche, growing not just when opportunities arise but when they make sense, after its leader changed careers to keep the family business from changing hands.

Read MoreInside the Florida Recycler Taking on NPE’s 100% Scrap Reuse Goal

Hundreds of tons of demonstration products will be created this week. Commercial Plastics Recycling is striving to recycle ALL of it.

Read MoreRead Next

Making the Circular Economy a Reality

Driven by brand owner demands and new worldwide legislation, the entire supply chain is working toward the shift to circularity, with some evidence the circular economy has already begun.

Read MoreFor PLASTICS' CEO Seaholm, NPE to Shine Light on Sustainability Successes

With advocacy, communication and sustainability as three main pillars, Seaholm leads a trade association to NPE that ‘is more active today than we have ever been.’

Read MoreSee Recyclers Close the Loop on Trade Show Production Scrap at NPE2024

A collaboration between show organizer PLASTICS, recycler CPR and size reduction experts WEIMA and Conair recovered and recycled all production scrap at NPE2024.

Read More