Film Extruder Tries Do-It-Yourself Electric Power

One of the country’s largest makers of stretch film and bags, the Sigma Plastics Group based in Lyndhurst, N.J., has embarked on an experiment in generating its own electricity.

One of the country’s largest makers of stretch film and bags, the Sigma Plastics Group based in Lyndhurst, N.J., has embarked on an experiment in generating its own electricity. Last year Sigma leased a small gas-fired power-generating plant from Honeywell, which installed the plant in Sigma’s Lyndhurst industrial park.

Honeywell Home and Building Control in Morristown, N.J., runs and maintains the co-generating plant for Sigma under a seven-year lease and a management contract. Honeywell’s contract includes an on-site engineer and 24-hr surveillance of the power plant by Honeywell.

The package represents an investment of $6.5 million for Sigma, but after the lease expires, Sigma will own the equipment. Sigma ultimately will save a lot on energy because Honeywell guarantees at least $1.2 million/yr in cost savings after the lease is up. That includes Honeywell’s $400,000/yr contract to continue running the plant.

Sigma had also expected to achieve modestly positive cash flow during the seven-year lease. The “co-gen” plant was supposed to save about $100,000/year in energy cost almost immediately. But that was before natural gas prices soared.

When Sigma struck the deal with Honeywell, natural gas cost about $2.80 a decatherm. But no sooner did Sigma fire up its co-gen plant last November, than natural-gas prices soared. In December, January, and February, gas hit all-time highs of over $10 a decatherm. That meant that in the short term, generating its own power wouldn’t save Sigma much, if anything, over buying electricity on the outside.

Methane next door

But Sigma wasn’t daunted. And it isn’t waiting around for the seven-year lease to end or for gas prices to drop. Sigma is already exploring a deal proposed by its next-door neighbor, the Kingsland Landfill, which could supply enough methane gas from the landfill to fire Sigma’s co-gen plant. The landfill currently flares off almost exactly the same amount of methane as Sigma uses in natural gas, says Bob Silk, Honeywell’s on-site technical-resource manager. The co-gen engines, which are built by Jenbacher AG in Austria, can be readily converted to run methane and frequently are methane-fired in Europe, Silk says.

Sigma Plastics operates 19 plants in the U.S. and three in Canada. Its Lyndhurst campus was chosen for the co-gen experiment not because it is such a big energy user, but because its energy is expensive. Lyndhurst houses Sigma headquarters and three film and bag-making plants processing 90 million lb/yr of stretch film, T-shirt bags, and merchandise and produce bags. It consumes about $250,000 a month of electricity. Sigma’s stretch-film plant in Kentucky processes a lot more resin—120 million lb/yr. But whereas power in Lyndhurst costs 8-9¢/kwh, power in Kentucky costs only 4-5¢/kwh.

Chilled water ‘for free’

The gas-powered engines provide enough hot water to power a 900-ton chiller, also installed by Honeywell as part of the co-gen plant. The heat-recovery boiler produces hot water at 210 F, which provides heat absorption for the chiller that supplies cooling water to all three buildings. That chiller replaces three electrically powered chillers, which were expensive to run. “Now chilling the water doesn’t use electricity. It’s entirely a byproduct of heat generated by the co-gen plant,” explains Mark Teo, Sigma’s executive v.p.

The co-gen plant should provide more reliable power, too. It generally runs around the clock, except for a week in July and a week in December when Sigma closes. The co-gen equipment at Sigma consists of two 1400-kwh gas-fired engines capable of generating a total of 23,000 Mwh/yr. They will supply about 70% of Sigma’s power needs in Lyndhurst.

Sigma is probably already one of the first plastic processors to generate its own power. If the landfill pipeline goes through, Sigma would almost certainly be the first to tap methane from a landfill.

Related Content

Reduce Downtime and Scrap in the Blown Film Industry

The blown film sector now benefits from a tailored solution developed by Chem-Trend to preserve integrity of the bubble.

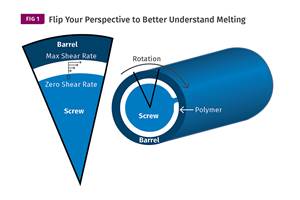

Read MoreUnderstanding Melting in Single-Screw Extruders

You can better visualize the melting process by “flipping” the observation point so the barrel appears to be turning clockwise around a stationary screw.

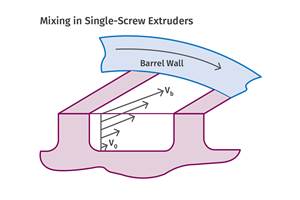

Read MoreSingle vs. Twin-Screw Extruders: Why Mixing is Different

There have been many attempts to provide twin-screw-like mixing in singles, but except at very limited outputs none have been adequate. The odds of future success are long due to the inherent differences in the equipment types.

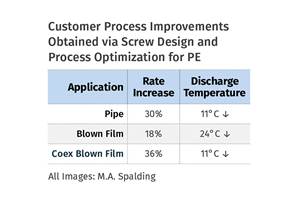

Read MoreHow Screw Design Can Boost Output of Single-Screw Extruders

Optimizing screw design for a lower discharge temperature has been shown to significantly increase output rate.

Read MoreRead Next

See Recyclers Close the Loop on Trade Show Production Scrap at NPE2024

A collaboration between show organizer PLASTICS, recycler CPR and size reduction experts WEIMA and Conair recovered and recycled all production scrap at NPE2024.

Read MoreBeyond Prototypes: 8 Ways the Plastics Industry Is Using 3D Printing

Plastics processors are finding applications for 3D printing around the plant and across the supply chain. Here are 8 examples to look for at NPE2024.

Read MorePeople 4.0 – How to Get Buy-In from Your Staff for Industry 4.0 Systems

Implementing a production monitoring system as the foundation of a ‘smart factory’ is about integrating people with new technology as much as it is about integrating machines and computers. Here are tips from a company that has gone through the process.

Read More