Single vs. Twin-Screw Extruders: Why Mixing is Different

There have been many attempts to provide twin-screw-like mixing in singles, but except at very limited outputs none have been adequate. The odds of future success are long due to the inherent differences in the equipment types.

Mixing in single screws is first limited by the channel(s) the polymer follows down the screw. The shear rate and resultant downstream velocity is maximum at the barrel or the top of the channel and minimum or potentially zero at the screw root.

I’m frequently asked why the mixing or compounding performance of a counter-rotating parallel twin can’t be duplicated on a single-screw extruder. Let me try to explain why.

First and foremost, the twin can essentially transfer the entire channel full of polymer from one screw to the other multiple times, permitting full-channel mixing. This can be done while imparting little shear to the bulk of the transferred polymer and very high shear to just a small segment of the polymer by simply changing the opposing channel depths or with mixing lobes. Additionally, the screws are run starved so that there is available volume for such transfers. It’s also done with very little pressure drop and resultant loss of output due to the intermeshing flights.

In single screws the pressure drop through high-shear areas — necessary for intensive mixing — is a limitation due to the loss of output and elevation of melt temperature. By repeating that process multiple times, the twin mixing can be made quite intensive and complete without overheating. Regardless of the extruder type, intensive mixing with high shear is required to fully disperse additives or even other polymers as many materials are only partially miscible in one another or form agglomerates that require high shear to break them up.

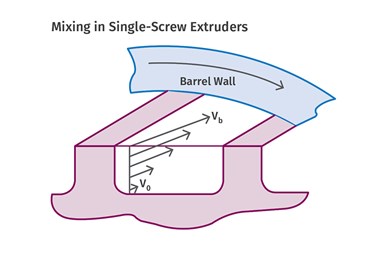

Mixing in single screws is first limited by the channel(s) the polymer follows down the screw. The shear rate and resultant downstream velocity is maximum at the barrel or the top of the channel, and minimum or potentially zero at the screw root. Because the polymer strongly adheres to the barrel and screw surfaces after melting, the shear developed by the polymer rotating with the screw in the barrel is the moving force. Essentially, in a force balance on the polymer the barrel is rotating around the screw and the moving surface of the barrel in contact with the polymer provides the transport. In the accompanying figure, these are shown as Vb and V0 .

Some stratification of velocity also results in only partial “turnover” of the polymer in the channel. That alone makes it difficult to completely mix the contents of the screw channel. Additionally, the channel contents tend to stay in relatively the same radial position in the single-screw channel due to continuing shear thinning of the viscosity decreasing from the barrel to the screw root.

Flow Resisters Raise Temperature, Lower Output

To try to overcome this limitation, various types of mixers and additional flights are used to offer some interruption and redirection of the polymer melt flow. However, these devices cause resistance to flow and reduce output as well as elevating melt temperature. All the polymer must flow through such devices repeatedly for uniformity of mix.

Mixing in single screws is first limited by the channel(s) the polymer follows down the screw.

Twin screws can apply high shear in small increments through multiple changes in channel depth and/or mixing lobes while subjecting the overall melt mass to limited shear. This is difficult and in most cases impossible with the single screw as it requires a tight clearance or restriction in the channel to develop the high shear rates.

Single screws must have essentially specific channel depths to reach their desired output and melt temperature. This limits the use of multiple high shear areas that are so useful in twin screws because of the screw-to-screw turnover that permits high shear on a small portion of the polymer by transferring the polymer to the other channel.

What the Maddock Mixer Does

There are many single-screw mixing and barrier flight designs that deliver some increment of mixing in single screws, although most primarily assist in melting by blocking passage of unmelt. Interestingly, one of the earliest and most prevalent mixers used with single screws is the Maddock-type mixer, which combines the two principles of the twin screw. One is the full “turnover” of the entire melt and the application of short-term high shear as the polymer passes over a barrier from inlet to outlet flutes.

I was fortunate enough to be involved in some of the early manufacturing of the Maddock mixers and testing at the Union Carbide lab in New Jersey. The features of twin-screw mixing were considered at the time in the design. The mixer concept was originally patented by Gene Leroy of Union Carbide and then further developed and popularized by Bruce Maddock. It featured complete turnover of the polymer and limited amounts of high shear.

Although quite effective in principle, it is limited to mostly a “one-shot” application because its inherent pressure drop reduces output and increases melt temperature enough that use of multiple sections was difficult. There are also spiral Maddock designs, but they only offer a slight improvement in pressure drop. Many of the other single screw mixers simply divide the melt at low shear, basically homogenizing the temperature without the high shear necessary for intensive mixing.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Jim Frankland is a mechanical engineer who has been involved in all types of extrusion processing for more than 50 years. He is now president of Frankland Plastics Consulting LLC. Contact jim.frankland@comcast.net or 724-651-9196.

Related Content

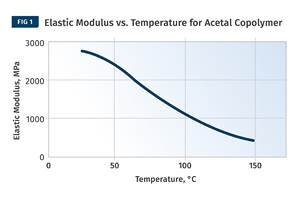

The Effects of Time on Polymers

Last month we briefly discussed the influence of temperature on the mechanical properties of polymers and reviewed some of the structural considerations that govern these effects.

Read MoreThree Key Decisions for an Optimal Ejection System

When determining the best ejection option for a tool, molders must consider the ejector’s surface area, location and style.

Read MoreFundamentals of Polyethylene – Part 6: PE Performance

Don’t assume you know everything there is to know about PE because it’s been around so long. Here is yet another example of how the performance of PE is influenced by molecular weight and density.

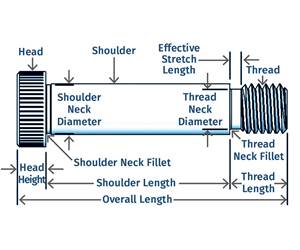

Read MoreWhy Shoulder Bolts Are Too Important to Ignore (Part 1)

These humble but essential fasteners used in injection molds are known by various names and used for a number of purposes.

Read MoreRead Next

For PLASTICS' CEO Seaholm, NPE to Shine Light on Sustainability Successes

With advocacy, communication and sustainability as three main pillars, Seaholm leads a trade association to NPE that ‘is more active today than we have ever been.’

Read MoreBeyond Prototypes: 8 Ways the Plastics Industry Is Using 3D Printing

Plastics processors are finding applications for 3D printing around the plant and across the supply chain. Here are 8 examples to look for at NPE2024.

Read MoreMaking the Circular Economy a Reality

Driven by brand owner demands and new worldwide legislation, the entire supply chain is working toward the shift to circularity, with some evidence the circular economy has already begun.

Read More

.jpg;width=70;height=70;mode=crop)