Mulch Film Goes High-Tech

Mulch films come in a dazzling array of colors and multi-layered structures designed to manipulate light, temperature, and moisture and repel insects. But high-tech films are expensive and have found only niche markets so far. Processors now think coextrusion, downgauging, and better field testing can put this market on a fast-growth track.

Test fields in Florida, Pennsylvania, and elsewhere are looking a lot like the Star Spangled Banner these days. They are bright with red, white, and blue experimental mulch films that are being tested for their impact on plant growth, crop yield, and even on the flavor and color of produce. But the main effect of colored mulch is to extend the growing season, so that domestic growers of tomatoes, melons, and eggplants can compete against the far longer growing season in Latin America.

These stripes of color on fruit and vegetable patches are signs of the widespread creative effort that processors, additive producers, and university researchers are devoting to agricultural films. Thinner gauges, higher line speeds, more complex multi-layer structures, and new pigment and additive formulations are some of the approaches being tested in the hope of persuading farmers to trade up from generic black and white films to more sophisticated—and pricier—products.

In the past decade, high-tech mulch films have been fine-tuned to manipulate light waves through different resin layers, colors, and additives. Wavelength-selective films can add days or weeks to a growing season and increase crop yields 20-30% more than conventional black mulch, which just retains moisture and warmth and keeps weeds down.

“In the Northeastern U.S. or Canada, the benefits can be very dramatic,” says Jodi Fleck-Arnold, senior product development engineer at Pliant Corp. in Schaumburg, Ill., a large producer of cast and blown mulch films. “Colored mulch films can add as much as one or two weeks to the growing season.”

But they’re expensive and difficult to make, and the results have not been consistent. “One year you might get 20% greater productivity, and the next year not,” says Peter Bergholtz, owner of Ken-Bar Inc., an agricultural film dealer in Reading, Mass.

Down-and-dirty no more

When mulch film first appeared in the early 1960s, it was a secondary product dreamed up by makers of PE diaper film because it could be made on the same cast-film lines and even on the same embossing rolls. Most mulch film is now blown, though some is cast. Either way, it is typically embossed with little bumps to give a rubbery feel and make it stretchable over the soil.

Mulch films are mostly blends of LDPE and LLDPE, though Sonoco Products in Hartsville, S.C., makes HMW-HDPE versions. Most mulch film is black for weed control, white for cooling, or black and white to do both.

Israel pioneered the first colored mulch films for light-spectrum modification to raise plant yields. “These films are how the Israelis made the desert bloom,” notes Bergholtz. Colors were first introduced in Europe a decade ago and were expected to take over 20% of the market. Instead, colored mulch film has remained largely developmental.

But that could change as results come in from new multi-year field testing of colored films. For example, masterbatch maker Ampacet Corp. is sponsoring testing of colored films at six sites, including Penn State Univ. in Rock Springs, Pa., and the Univ. of Florida in Apopka. These tests will help characterize when and where colored mulch film performs best.

Meanwhile, processors are downgauging mulch film from 3 mils to 1.5 mils or from 1-2 mils to fractional gauges. They are also busy developing new products such as “thermic” colors. Thermic films allow near-infrared light to pass through the film and into the soil, warming the soil more efficiently than does conventional IR-absorbent black film.

For example, Pliant is developing a fractional-gauge, multi-layer, cast mulch film that will be commercial next spring. The firm also plans to introduce blue and thermic-olive films next year. Sonoco is commercializing 0.4-0.5 mil black film and is developing a thermic olive-green film. Reyenvas S.A., a maker of three-layer blown mulch films in Seville, Spain, uses metallocene LLDPE to reduce film gauge from 2 mils to fractional gauge.

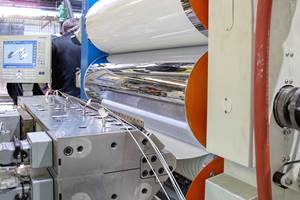

Processors are also raising outputs by increasing web widths and line speeds. Last spring, Pliant Corp. installed a $7-million Black Clawson coextruded mulch-film line at its Washington, Ga., plant. The line has such high output that it replaces several older lines. To take maximum advantage of that high productivity, Black Clawson designed a special automatic handling system that removes finished rolls from the winder and recores empty shafts.

Photo-selective plastics

Photo-selective mulch films let certain wavelengths of light through and absorb or reflect other wavelengths. These films are designed for a specific crop, time of year, climate zone, rainfall level, amount of sunlight, altitude, and exposure to insects. Photo-selective films include thermics, which pass IR heat into the soil, and selective-reflective mulches (SRM), which bounce uv light back into the plant while keeping the soil cool.

Thermic films are generally colored olive-green or brown. They can’t be black because carbon black effectively absorbs all light and then radiates up and down. Nor can thermics be white or silver, which tend to reflect all or most light.

Clear mulch films can be either thermic or just a “solarization” film that passes all light through. Either way, clear film creates extremely high temperatures underneath, which kill weeds.

SRM films can be colored or white. They incorporate clear chemical IR blockers, which don’t allow active photosynthetic radiation to pass through the film, so weed seedlings don’t grow.

Thermics are most applicable in the Northeast or during winter planting in the South. SRM films keep the soil cool and are most applicable to hot conditions in the South and mid-summer in the Northeast.

In a hot climate like Florida, with 140 kly (kilo-Langleys/year) of sunlight and 160 kly at the southern tip, a photo-selective colored mulch could make soil too warm. In Florida, growers use mulch film primarily to control weeds and hold moisture in the soil. A typical Florida film would be a monolayer white in summer to cool the soil and coextruded white over black in late summer. Both the black and white Florida films need a lot of uv stability to withstand high temperatures.

Pennsylvania, with only 120 kly of sunlight, is a good location for a thermic colored film that passes IR waves into the soil. Because the thermic color passes heat through rather than absorbing it, the film stays cooler than does a black film and needs less uv stabilizing. Therefore, film designed for Florida will survive in Pennsylvania, but not vice versa.

At high altitudes, where sunlight is more intense, films should absorb uv to avoid burning crops.

In cooler climates, mulch films are often used in greenhouses. A glass or plastic greenhouse cover can allow use of a less expensive mulch film that does not contain special additives. However, glass and plastic differ in the wavelengths they transmit. So the type of greenhouse cover must be taken into account when formulating a mulch film, says John Ven Meervenne, sales manager at Hyplast Ltd., a pioneer in colored mulch films, located in Hoogstraten, Belgium.

The color factor

For reasons that are not fully understood, visible light reflected from colored films can enhance fruit and vegetable growth, strengthen plant stems, encourage fruit to grow lower down on plants, and keep insects away.

Development work at Penn State uses green mulch to encourage development of stronger plant stems to support more fruit. Red and blue mulch films apparently stimulate phytochromes, the mechanism in plant leaves that senses light in the 580-700 nm range. Different ratios of “far red” (700-740 nanometers) and “red” (580-640 nanometers) trigger different morphological responses in the plant and/or the fruit, which can help produce bigger fruit. The latest color research from the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture in Clemson, S.C., suggests that colored films can even enhance the flavor of some root vegetables like radishes.

The effect of color in mulch films is specific to particular plants. Sonoco has licensed a particular red hue patented by the USDA for its effect on tomatoes and peppers. Red mulch encourages tomato plants to produce more fruit by reflecting light in the red and far-red spectrum (580-700 nm) back onto the leaves and developing fruit.

“Green is best with peppers and melons. Red is doing well with tomatoes. Blue does well for squash and eggplant,” says Michael Orzolek, professor of vegetable crops at Penn State. He heads an Ampacet-funded color-research program. On the other hand, Prof. James Marion White at the Univ. of Florida, who also receives Ampacet funds to study color effects on plants, has found no benefit from red, green, or blue on crops in that state. Orzolek explains that colored films are most successful in cooler parts of the country. “We’re seeing responses to colors anywhere north of Virginia,” he says.

Silver is another story, however. Silver-sided mulch is popular for melons and strawberries in the Southeast, where in midsummer a red or black mulch would get so hot it could burn the fruit. Solplast S.A., a maker of three-layer blown mulch films in Lorca Murcia, Spain, sells a lot of silver/black film for melon growing in Spain and shies away from reds because of the hot climate.

Clarke Plastics in Greenwood, Va., makes a metalized silver mulch for vegetables. Highly reflective silver drives insects away, though the mechanism isn’t fully understood. It’s believed that reflecting uv “b” wavelengths makes plants invisible to pests like thrips, aphids, or white fly, so they don’t land on the plants and spread mosaic virus. But reflecting uv “b” wavelengths also makes it harder for bees to find the flowers and pollinate them. But Solplast in Spain says it found a way to create a balanced reflectance that “blinds” the white flies but not the bees. To help processors tailor silver films’ reflectivity, A. Schulman recently introduced two silver mulch-film concentrates designed to provide 35% to 55% reflectivity.

Coextruded yellow/brown mulch film is marketed in South America. Yellow side up attracts insects, while the brown side beneath retains heat. When the film heats up, it burns and kills the insects attracted to the yellow color. Farmers can also lay a band of yellow plastic down every fifth row in a field to draw the insects away from the plants. Then the farmers need spray only the yellow rows, using 80% less insecticide.

But plants and bugs aren’t the only ones affected by colors. Farm workers react too. Silver mulch can blind a tractor driver as well as a white fly, one researcher notes. Silver is also extremely hot to work near. Meanwhile, Belgium’s Hyplast found that using red film in greenhouses in Northern Europe gave workers headaches, even though the tomatoes liked it.

New tricks with layers

Creative coextrusion can also reduce film cost and add functionality. For example, Pliant recently launched a mulch film that’s black on one side and has a single wide white stripe on the other, putting the expensive TiO2 directly under the plants where it’s needed.

Penn State’s Orzolek proposes the idea of coextrusions in which the top layer or color breaks down and disappears by the end of the first planting to expose a second color underneath for a second planting. “You could have blue on top of white for spring planting. As the summer heats up, the blue layer could disappear, leaving the white layer, which keeps the soil cooler for a second planting in August,” he suggests. The white layer reflects IR rays, so new seedlings don’t get too warm under the film. Such a structure is more economical because it gets two plantings out of one installation of film.

Mulch films can also act as a barrier to contain methyl bromide, a poisonous gas injected into the soil to kill bacteria. Such soil fumigation is important for a number of crops, including tomatoes, strawberries, and tobacco. While good for crops, methyl bromide is harmful to the atmospheric ozone layer. Consequently, regulators in California and several European countries are trying to phase it out.

A high-barrier mulch film over the soil could allow farmers to use less methyl bromide. There are alternatives to methyl bromide that are less harmful to the ozone, but they are also less effective. An impermeable mulch film could improve the effectiveness of these gases by keeping them in contact with the soil longer.

In Europe, regulators have created a film classification called “VIF” (virtually impermeable film), which transmits no more than 0.2 g/hr of soil-sterilization gases. An example of VIF film is a product from Belgium’s Hyplast that is believed to be the only seven-layer, high-barrier mulch film in the world. This blown film uses double layers of mLLDPE around nylon in a structure of mLL/mLL/tie/nylon/ tie/mLL/mLL. Though it’s made in Europe, the product is marketed in the U.S. through a sister company, Klerks Plastic Products in Ridgeburg, S.C.

Processors are considering even more layers. For example, Pliant’s new high-output mulch-film line in Georgia is the first installation of Black Clawson’s new Microlayer feedblock, which can create up to 14 layers. Users multiply layers by changing pins in the feedblock to split existing layers into two. With it, Pliant has developed a new black/white film with zero light transmission and up to 60% reflectivity. The feedblock lets Pliant stack thin layers of up to four materials, increasing opacity in the black layer and reflectivity in the white, while permitting downgauging relative to traditional films. “In a film that thin, it’s hard to get zero transmission and not have the black layer show through the white,” says Pliant’s Fleck-Arnold.

Several smaller U.S. producers make three-layer barrier films of nylon/tie/PE or PE/nylon/PE. In the latter, the nylon is blended with a little adhesive. This diminishes the nylon’s barrier properties, but lets it adhere directly to PE, says William Hellmuth, senior product manager at Battenfeld Gloucester.

Related Content

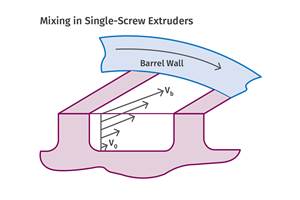

Single vs. Twin-Screw Extruders: Why Mixing is Different

There have been many attempts to provide twin-screw-like mixing in singles, but except at very limited outputs none have been adequate. The odds of future success are long due to the inherent differences in the equipment types.

Read MoreRoll Cooling: Understand the Three Heat-Transfer Processes

Designing cooling rolls is complex, tedious and requires a lot of inputs. Getting it wrong may have a dramatic impact on productivity.

Read MorePart 2 Medical Tubing: Use Simulation to Troubleshoot, Optimize Processing & Dies

Simulation can determine whether a die has regions of low shear rate and shear stress on the metal surface where the polymer would ultimately degrade, and can help processors design dies better suited for their projects.

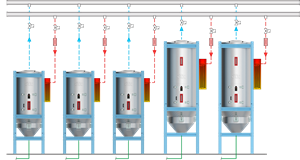

Read MoreHow to Effectively Reduce Costs with Smart Auxiliaries Technology

As drying, blending and conveying technologies grow more sophisticated, they offer processors great opportunities to reduce cost through better energy efficiency, smaller equipment footprints, reduced scrap and quicker changeovers. Increased throughput and better utilization of primary processing equipment and manpower are the results.

Read MoreRead Next

People 4.0 – How to Get Buy-In from Your Staff for Industry 4.0 Systems

Implementing a production monitoring system as the foundation of a ‘smart factory’ is about integrating people with new technology as much as it is about integrating machines and computers. Here are tips from a company that has gone through the process.

Read MoreLead the Conversation, Change the Conversation

Coverage of single-use plastics can be both misleading and demoralizing. Here are 10 tips for changing the perception of the plastics industry at your company and in your community.

Read MoreFor PLASTICS' CEO Seaholm, NPE to Shine Light on Sustainability Successes

With advocacy, communication and sustainability as three main pillars, Seaholm leads a trade association to NPE that ‘is more active today than we have ever been.’

Read More