New Cure for the Headaches of In-Mold Labeling/Decorating

New IML/IMD method combines the best aspects of precut label stacks and labels on a roll with none of their drawbacks.

If you’re an injection molder who wants to increase efficiency in decorating by applying labels or decals in the mold rather than post-molding, you have two choices:

• Option 1. Buy labels on a roll and die-cut them at the press before loading them into the tool. That means you have to gain expertise in diecutting, install bulky equipment by the press, and concern yourself with knife-sharpening schedules, spare knives, and more. That’s why most IML/IMD processors choose the alternative:

• Option 2. Buy precut labels in stacks and load them into fixtures, or nests, for robotic delivery to the mold. That brings a whole set of its own issues, such as the need for antistatic treat- ment of labels to keep them from sticking to one another, which competes with the need to apply a static charge to the labels to hold them in place in the tool. Mis-picks, doubles, crooked or upside-down labels, and dropped labels are often the result. Static problems vary with changes in humidity. And there is also the delivery of precut labels from the printer in bundles wrapped with bands, which means the five to 10 labels at the top of every stack are often discarded because they are dented by the wrapper band. All these issues are magnified by the industry trend to thinner labels, which are harder to handle, and to shorter runs of a larger number of SKUs, which means more changes of label magazines and other setup variables.

“Destacking and static electricity are the No. 1 cause of IML scrap—and that’s molded scrap, which means you have lost both the label and the part,” cautions Bob Travis, president of inkWorks Printing LLC, a supplier of IML labels in Plymouth, Wis. “There are so many variables in labels for the molder to deal with,” Travis concedes—different lots, the labels’ age and position in the stack, and some labels’ multi-layer structure, which can cause them to curl, as well as the need to change labels when changing jobs. In high-humidity, worst-case circumstances, scrap rates can be as high as 20%, though a well-run operation would typically have less than 2% scrap All these factors led to a collaboration between inkWorks and two automation suppliers, CBW Automation, Fort Collins, Colo., and Robotic Automation Systems, Waunakee, Wis., to come up with a third and better way to accomplish IML and IMD.

Travis calls it “perf-in-place labels,” and Robert Harvey, v.p. of sales and marketing for CBW Automation, calls it “precut, roll-fed IML.” The secret is delivering labels on a roll, but already die cut so that 98% of each label’s periphery is precut and the label is held in place only by narrow tabs 0.011 in. wide, three to five tabs on a side of a 3-in.-wide label. In this way, labels can be pulled out of the web easily by a robot for delivery directly to the tool, with no intermediate stacking.

InkWorks supplied perf-in-place labels as far back as six years ago, but in sheet form. A version of the new roll-fed approach was exhibited at NPE2015, where a CBW side-entry robot picked the labels out of the web and placed them in the mold (see June ’15 show report here and here). CBW’s new “standalone” unwind system for roll-fed precut labels can be integrated with the user’s choice of label- and parts-handling automation.

RUNNING WITH ZERO SCRAP

The first user of CBW’s new stand-alone format is custom molder Commercial Plastics Co. (CPC), based in Mundelein, Ill., with three plants, over 320 employees, and 130 injection presses from 55 to 2000 tons. Its $75 million business is distributed among medical- waste management, agriculture, consumer products, commercial laundry, health and fitness, and CD/DVD packaging.

CPC installed the first of the new IML systems in July at its Kenosha, Wis., plant and a second started up in September. CPC had used robots from Robotic Automation Systems for 10 years to perform IML with precut stacked labels and therefore approached this vendor when it was looking for a better approach. For CPC, a critical IML application is PP medical-waste bins, molded in 2-, 3-, 4-, and 8-gal sizes with four labels per part (supplied by inkWorks). Because these safety-related products are tightly regulated, the labels have sequential barcodes, which makes labeling errors a molder’s nightmare. “The big problem with sequential barcoding is it’s easy to lose sequence with stacked labels—but not with this new system,” states CPC president Bill O’Connor. “Perforated labels eliminate many modes of failure. Now it’s impossible to end up with two different barcodes on a product, which is priceless to the customer.”

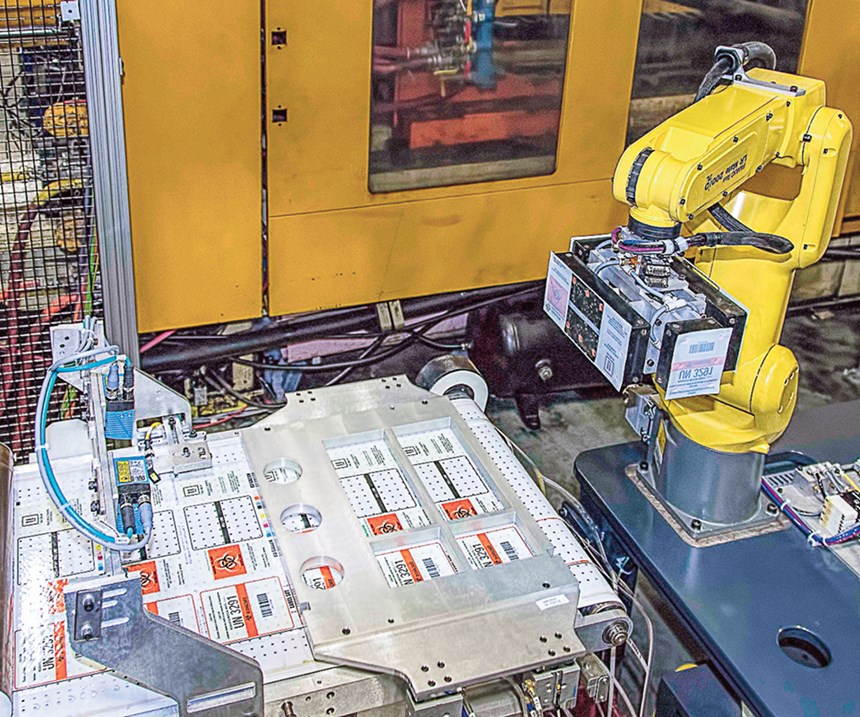

The new IML system is based on the label dispensing system from CBW Automation, which indexes four labels at a time. It comprises a vacuum table with a mechanical hold-down frame to hold the labels in place and flatten out kinks, and a barcode reader that checks labels’ barcodes. The vacuum conveyor is servo-controlled with two-axis positioning.

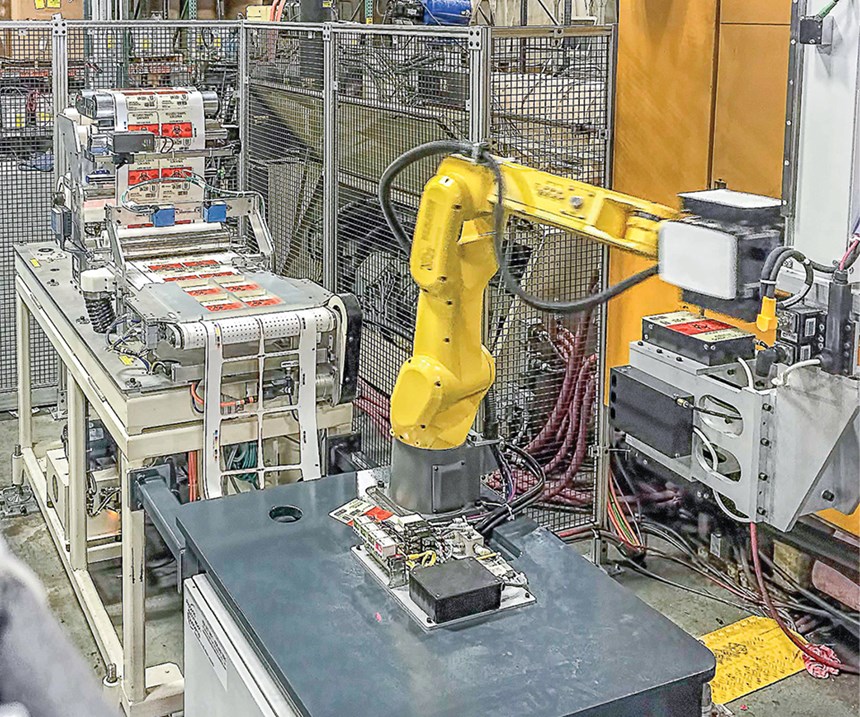

The robotic label pick-and-place system is integrated with the CBW conveyor by Robotic Automation Systems. The first system at CPC is designed for a two-cavity mold. A six-axis Fanuc articulated robot plucks four labels for one part, using rotating, four-sided end-of-arm tooling (EOAT). The Fanuc LR Mate robot hands off the labels to a three-axis, top-entry Cartesian robot from WEMO Group of Sweden. The WEMO robot waits while the six-axis robot goes back to the web to pick a second batch of four labels for the other mold cavity. Once the three-axis robot has its full complement of eight labels, it inserts them into the mold cavities, where they are statically charged to hold them in place. Both robots have vacuum confirmation to detect loss of suction or absence of a label. Parts are ejected with a free drop. Typical cycle time for these heavy-wall parts is around 45 sec in a Husky 500-ton Hylectric hybrid press.

Craig Tormoen, president of Robotic Automation Systems, notes that each robot and the CBW dispensing system has its own controller to be used for setup, but there is also a single point of control while the system is up and running, consisting of a PLC and operator interface that talk to the other components.

Tormoen notes that while the first system was designed for a two-cavity mold, the second system is for a single cavity. The latter has simpler automation, with only a single three-axis WEMO robot, not requiring the handoff from a six-axis Fanuc robot.

O’Connor is delighted with the performance of the system, which had been running for two months at press time with zero rejects. It is unaffected by humidity or by the curl of laminated labels (which have to withstand 500 wash cycles). It has no difficulty handling thinner labels, which save money and allow for easier overmolding.

Changing labels requires a change in the CBW system’s hold-down plate and robot EOAT, but there’s no more need for a new set of label magazines with unique guarding. “This system is more flexible,” O’Connor says. “It can run three different jobs that have the same web width. We just change the hold-down and touch a button on the control to call up a new operating program. There’s less downtime and tooling cost. Before now, we had to wait for the automation change-over to run a new part. Now, we can change the automation faster than we can change the injection mold. In effect, that opens up more capacity for us.”

In addition, the robots in the system are standard, not dedicated, models, which can be used for other purposes if an IML job is not running. O’Connor concedes that the new system requires the press to stop while changing rolls of labels, unlike a cut-and-stack IML system. On the other hand, a roll holds 2000 labels, vs. 200 in a typical label stack. “So we change label rolls from twice a day to every two days, instead of refilling stacks every hour or two.”

He also notes that the new system is more expensive initially than a cut-and-stack IML system. But he considers it cost-effective, with an ROI estimated at one year or less—although CPC has shared some of the savings with its customers. “Dedicated label magazines are not cheap,” he notes. He adds that thinner labels cut costs (as does the elimination of antistat), since the label can account for half the cost of a container. What’s more, the label-on-a-roll system helps keep control in an environment of short runs of an increasing number of SKUs: “You don’t have to keep track of innumerable stacks of different labels in your shop.”

O’Connor’s bottom line is that he’d prefer to use the precut, roll-fed system for every IML job, except perhaps for a stack mold with many cavities, which might take too long for the robot to load with labels. O’Connor is talking to other customers about using the new system in parts other than medical waste bins. He sees the system as uniquely advantageous for smaller parts with smaller labels, which are more difficult to handle in precut stacks.

The labels currently used in the system are PP based, and CPC regrinds the leftover web skeleton and blends it into other PP parts (ones that are colored black). The partners are now testing polycar bonate labels for parts molded of similar resin.

Related Content

Transforming Laser Marking Operations With Collaborative Robotic Automation

FOBA partners with Flexxbotics and Universal Robots.

Read MoreA Guide to Ultrasonic Welding Controls

Ultrasonic welding today is a sophisticated process that offers numerous features for precise control. Choosing from among all these options can be daunting; but this guide will help you make sense of your control features so you can approach your next welding project with the confidence of getting good results.

Read MoreNew Concept for HDPE Paint Pails With Plasma Coating, Digital Printing

NPE2024: Delta Engineering presented integrated systems for injection molding, barrier coating and printing HDPE paint pails.

Read MoreNext-Generation Workhorse Ultrasonic Welding Machines

NPE 2024: Rinco Ultrasonics’ line of standard ultrasonic welding machines significantly upgraded.

Read MoreRead Next

Beyond Prototypes: 8 Ways the Plastics Industry Is Using 3D Printing

Plastics processors are finding applications for 3D printing around the plant and across the supply chain. Here are 8 examples to look for at NPE2024.

Read MoreLead the Conversation, Change the Conversation

Coverage of single-use plastics can be both misleading and demoralizing. Here are 10 tips for changing the perception of the plastics industry at your company and in your community.

Read More