Extrusion: How to Adjust for Polymer Shrinkage and Orientation

Polymers shrink and orient. Sometimes orientation is unbalanced, resulting in misshaped parts. But there are steps beyond tweaking the die that can mitigate these effects.

Polymers shrink, and extrusion processors have to compensate for that effect to meet the dimensional and geometrical requirements of their parts. While it’s true that most materials shrink, polymers tend to shrink a lot more. They shrink due to the normal thermal expansion/contraction caused by heat, of course.

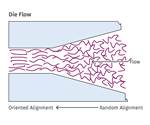

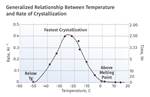

But they also have a second shrinkage stage, one that’s particularly pronounced in some semi-crystalline materials (and to a less extent in amorphous polymers). Semi-crystalline polymers shrink at a rate that can be six times higher than amorphous polymers. In their relaxed state, semi-crystalline polymers are structurally aligned for the most part, whereas the orientation of amorphous polymers is always completely random.

When melted, all polymers are in a random state. When cooled below their crystallization temperature, the ordered structure of the crystalline polymers starts to form. Amorphous polymers have a natural random chain orientation and require less realignment to reach their relaxed state when cooled after melting. Crystalline polymers, on the other hand, have to realign considerably to achieve their reorganization and packing for a relaxed structure. As a result, crystalline polymers shrink more as they reorient to their relaxed state. This is also accounts for the small change in density for amorphous polymers from the melt to the solid state, while crystalline polymers have a much greater density change.

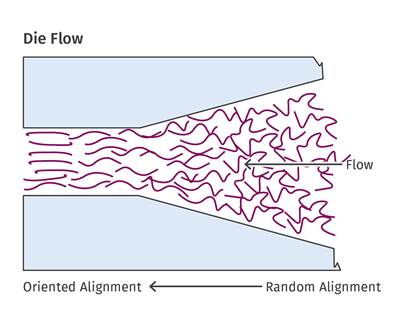

If this shrinkage effect accounted for all the dimensional changes that take place during extrusion cooling, processors would have a relatively straightforward means to adjust for the dimensional change in their parts. During processing, however, polymers in the melt condition are subjected to flow-induced stress orientation and mechanical stretching in the melted to semi-solid state as they are cooled. This results in the molecular structure becoming oriented proportional to the stress.

Why Not Cool Quickly?

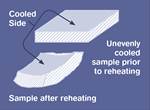

If cooled quickly by quenching, the polymers tend to retain some of the oriented structure; the mobility of the polymer chains gets “frozen in.” But when subjected to heat afterward, all polymers will eventually return to their relaxed state, even if that takes years if kept at a temperature low enough to reduce molecular mobility. That explains why extruded parts may not distort for long periods of time, but when subjected to an unusually high temperature will distort substantially.

If cooled quickly by quenching, the polymers tend to retain some of the oriented structure; the mobility of the polymer chains gets “frozen in.”

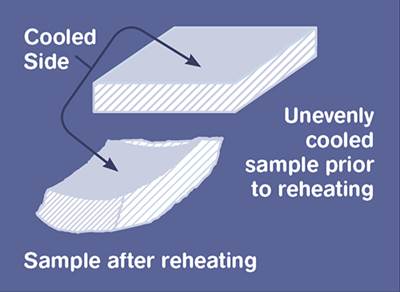

The more the polymer molecules are oriented, the more shrinkage will ultimately occur in that direction. Imagine a rubber sheet being stretched in just one direction. The difference in transverse and machine direction shrinkage is a visible indicator of how much unbalanced orientation is in the extruded part. This can be determined by cutting coupons, heating them and measuring the relative shrinkage. Because of this unbalanced stress it’s not unusual to see pipe that cracks in the sunshine, flat sheet that takes on a corrugated shape, lids that become oval and will not fit the cups, and profiles that bend and twist. All are due to unbalanced orientation with post-processing shrinkage.

Orientation is seldom uniform across the part cross-section due to varying drawdown, shear stress, and cooling rates across the part.

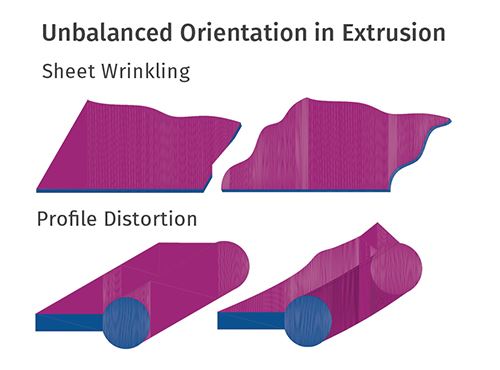

It’s impossible to eliminate all orientation in an extruded part without some sort of secondary annealing process that allows for complete relaxation of the polymer. The usual goal is to minimize the variation so a usable extruded part can be made without additional steps. See the accompanying illustration for some examples of unbalanced orientation.

Processors sometimes do not recognize the effects of unbalanced orientation and how to combat it.

In the case of the sheet, the middle had higher flow stress or orientation through the die because the die was pinched down more in the center than the edges. With uniform cooling across the sheet, the result is more residual orientation in the center than the edges, causing the sheet to shrink more in the middle. This results in both edges wrinkling up to match the length of the middle portion.

A similar situation exists in the profile. The thinner cross-section sees more flow-induced stress in the die and drawdown because of the narrower opening, resulting in more orientation in that section. Assuming uniform quench cooling, the thinner cross-section shrinks more than the less oriented circular section. This causes the part to distort as it seeks its relaxed state.

Combating Unbalanced Orientation

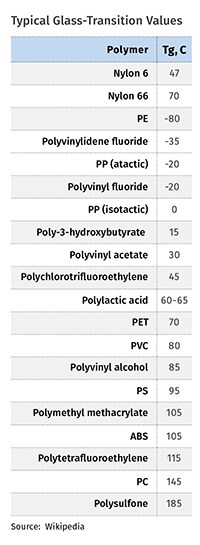

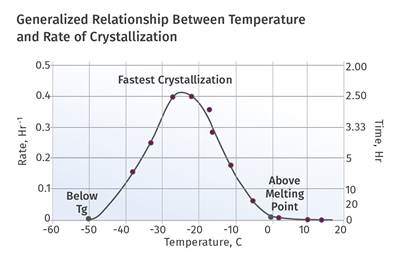

Processors sometimes do not recognize the effects of unbalanced orientation and how to combat it. As a result, they tend to make die adjustments with little success. Relaxation cannot occur below the glass-transition temperature (Tg), but many of the most useful semi-crystalline polymers have glass-transition temperatures well below room temperature (see table) so they continue to relax (shrink) indefinitely until they reach their equilibrium structure. With highly oriented parts, the unbalanced shrinkage can be as much as 50%, making for some severe distortion or even cracking to relieve the stress.

The biggest problem is that this distortion might not show up for several days, weeks, or even months, if the part was quenched quickly and is kept cool after processing.

Changing the part geometry is usually not an option to resolve the unbalanced orientation, so the operating conditions must be changed. In most cases, simply reducing the cooling rate and reducing the drawdown will alleviate much of the unbalance. For more difficult situations, zoned cooling, additional heating in the highly oriented sections, interruptions in the cooling phase to allow thermal homogenization, and, finally, secondary annealing steps may be required.

Related Content

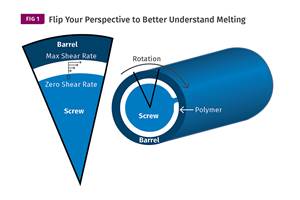

Understanding Melting in Single-Screw Extruders

You can better visualize the melting process by “flipping” the observation point so the barrel appears to be turning clockwise around a stationary screw.

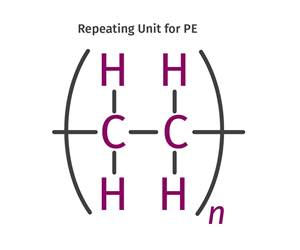

Read MoreThe Fundamentals of Polyethylene – Part 2: Density and Molecular Weight

PE properties can be adjusted either by changing the molecular weight or by altering the density. While this increases the possible combinations of properties, it also requires that the specification for the material be precise.

Read MoreFundamentals of Polyethylene – Part 6: PE Performance

Don’t assume you know everything there is to know about PE because it’s been around so long. Here is yet another example of how the performance of PE is influenced by molecular weight and density.

Read MoreBack to Basics on Mold Venting (Part 1)

Here’s what you need to know to improve the quality of your parts and to protect your molds.

Read MoreRead Next

Cooling Tips for Crystalline Polymers

If a little cooling is good, is a lot of cooling better?

Read MoreEXTRUSION: Orientation: The Good and the Bad

Depending on what you are trying to accomplish, molecular orientation can have a positive or negative impact on your part. Here’s how to control it.

Read MoreA Processor’s Most Important Job, Part 2: Crystallinity

Process conditions help determine the difference between the maximum degree of crystallinity that can be achieved in a polymer and the degree that is present in a molded part.

Read More

.jpg;width=70;height=70;mode=crop)