Get the Roll Surface Right

Roll finishes often cost more than the roll itself. The right finish improves film or sheet quality and raises output. Yet most processors don't know how to measure surface roughness or to specify it properly.

The correct surface finish on metal, chrome-plated, and ceramic-coated rolls does a lot to improve film and sheet quality. Conversely, an inappropriate roll finish can damage the product and slow output. If a roll is too rough, it can scuff the film or cause it to stick to the roll. If a customer wants a satin finish or texture and the roll is too smooth, the customer won’t get the product quality it wants. With thin films, too smooth a roll can also create a vacuum through lack of air release, causing the film to stick.

Surface roughness provides traction to pull the film, air release to keep film from sticking, and imparts surface texture, depending on the resin, gauge, heat, and pressure used. All rolls in a plastic film or sheet line have specific surface-finish requirements that depend on their function. Rolls with different finish requirements include chill rolls; stretch, nip, and polishing rolls; machine-direction orienters; and rolls for corona treating. They may be coated with one of several materials including chrome, nickel, ceramic, or sprayed metal.

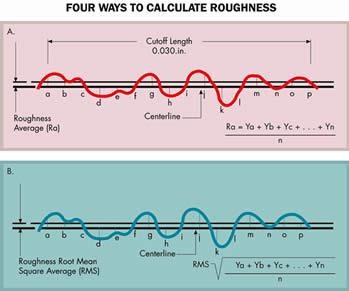

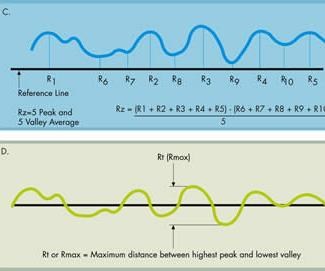

Roughness is commonly calculated using one of four methods: Ra (roughness average), RMS (root mean square), Rz (a 10 point average), and Rt or Rmax (maximum between peak and valley). Different methods can be combined to give more detail on roughness.

All four methods measure some combination of peak and valley distances in the surface texture and give results in either micro-inches or micro-meters (microns). A micro-inch is much smaller than a micron, so don’t confuse them. A micro-inch is one-millionth of an inch; a micron is one-millionth of a meter. So one micron is equal to 39.37 micro-inches. A finish that totals one micro-inch is finely polished while one that totals one micron is coarsely textured.

The most common measuring method is Ra or roughness average. Metal finishing rolls range from an Ra of 0 to 0.5 micro-inches for a highly polished mirror finish for optical-grade products, up to Ra 50 or 60 micro-inches for satin-finished products, or possibly as much as Ra 300 micro-inches for embossed or coarsely textured products. Ceramic coatings, which are porous, start at around Ra 2 micro-inches.

How rough is rough?

Roughness is measured by a profilometer, an easy-to-use, hand-held device available in a variety of sizes, shapes, stylus configurations, accuracy levels, and prices. Cost starts at around $2000 for a simple model and goes up for high-tech versions. Most units will give appropriate detail for plastics processing. Yet as important as these devices are, processors often don’t even own one.

All profilometers measure the physical depth of surface irregularities using some form of diamond or brush-type stylus attached to an arm that travels in a straight line for a specified “cutoff” or sampling length, typically 0.03 in. Most profilometers allow for various cutoff lengths. The profilometer transforms the information from the stylus into an electrical signal and converts that signal into usable data.

How do processors who haven’t measured roll roughness before know what roughness is right for them? A good starting point is to measure the Ra value on your existing rolls using a profilometer. Processors should take detailed measurements of any rolls they’re exceptionally happy with and duplicate those rolls. Processors can also show roll makers a sample of the film product with a surface texture or finish that they want to reproduce.

Most processors, however, order or refurbish a roll simply by specifying a finish such as “grind,” “fine grind,” “polish,” or “mirror.” All can be interpreted differently, except for a mirror finish, which means Ra 0 to 0.5 micro-inches. That leaves the door open for roll manufacturers to deliver specified rolls with a wide range of surface roughness.

Surface finishes are very costly, at times more expensive than the roll itself. Roll makers achieve different finishes by polishing for gloss, superfinishing for a mirror finish, or grit blasting. Varying the blast media, media size, nozzle size, pressure, and duration creates a wide range of textures from satin to extremely coarse.

The wrong finish costs as much to apply as the right one. Since film end users and converters are becoming more demanding, processors are expected to achieve more consistent clarity and surface finish and more sharply embossed textures.

Michael Hebert is general manager of the Perma-Flex Engineering Div. of Perma-Flex Roller Technology LLC in Orange, Mass., which builds and repairs rolls for cast and biaxially oriented film, blown film, and sheet.

Related Content

Extrusion Excellence: This Year's Top Stories

Revisit the year’s most popular articles on extrusion technology and processes, showcasing innovations, best practices, and the trends that captured the plastics processing community’s attention.

Read MoreBanach to Lead Cast Film, Sheet, Coatings at Reifenhäuser

Flat film and sheet veteran has worked for both suppliers and processors.

Read MorePTi Makes Changes in Leadership Structure

Moves aimed at bolstering the future of the sheet extrusion manufacturer.

Read MoreNew Owners for Alpha Marathon

After bankruptcy, new group purchases intellectual property and forms Alpha Marathon Film Extrusion Technologies.

Read MoreRead Next

Beyond Prototypes: 8 Ways the Plastics Industry Is Using 3D Printing

Plastics processors are finding applications for 3D printing around the plant and across the supply chain. Here are 8 examples to look for at NPE2024.

Read MorePeople 4.0 – How to Get Buy-In from Your Staff for Industry 4.0 Systems

Implementing a production monitoring system as the foundation of a ‘smart factory’ is about integrating people with new technology as much as it is about integrating machines and computers. Here are tips from a company that has gone through the process.

Read More