Medical Molder, Moldmaker Embraces Continuous Improvement

True to the adjective in its name, Dynamic Group has been characterized by constant change, activity and progress over its nearly five decades as a medical molder and moldmaker.

Covering 23,500-ft2, Dynamic’s molding operation has 80 employees and ui ISO 13485 certified and FDA registered.

Photo Credit: Dynamic Group

In an age where virtually everybody carries a device on their person that makes them instantly reachable, the rationale for a public address (PA) system has waned. Have a companywide message? Send a companywide email. Need to immediately get the attention of a specific worker? Send him or her a text.

While PAs have fallen into disuse at many businesses, at the Dynamic Group, the chirp as its broadcast system turns on remains a familiar sound. But instead of announcements seeing who left on the lights of their vehicle or forgot their phone in the bathroom, at Dynamic, the PA crackles on and strains of the English rock band Motörhead come across the speakers.

While there are certainly music lovers at the Minnesota-based injection molder and moldmaker, the reason “The Ace of Spades” might be playing isn’t about rock appreciation, in this case, it’s about the company’s continuous improvement (CI) plan. “When someone suggests an improvement,” Joe McGillivray, Dynamic’s CEO and owner, explains, “an audio clip that represents their team would play over the speaker, so everybody else in the company knew Team Motörhead had put another suggestion in.”

“The company looks completely different because the smartest people and the people that know the most about the business are making the changes on their own.”

It’s not just the CI program that makes use of the PA system. Dynamic also instituted a “Code” initiative where the speakers are used for companywide alerts. A Code Orange notifies an internal team to an instance of rework. “A button is pushed, and ‘Code Orange’ comes over the speakers,” McGillivray says. “A certain set of individuals would have to drop whatever they’re doing, go to a central location and start a formal process of identifying what Dynamic is going to do at this moment to deal with the problem.”

Now in its second generation after it was founded in 1977 as a toolmaking shop by Joe McGillivray’s father Peter and his partner David Kalina in the latter’s basement, Dynamic Group continues to involve and improve, including starting and then closing a separate quick-turn and prototype tooling business. There’s always been a focus on medical and molding throughout, whether for sampling tools or running production. Leaning into listening to its employees’ insights about the business (including through the CI program) has brought about fundamental, positive change, according to McGillivray.

“We’ve had thousands and thousands and thousands of improvements,” McGillivray says. “The company looks completely different because the smartest people and the people that know the most about the business are making the changes on their own.”

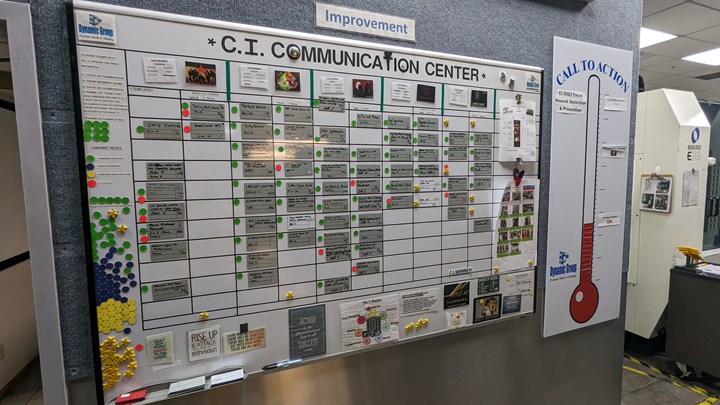

Dynamic Group estimates that its Continuous Improvement program has netted 1,200 improvements over the last 10 years, but the impact in many ways is immeasurable. Photo Credit: Dynamic Group

Suggestions Welcome

Dynamic’s CI and Code programs were both born out of visits with other manufacturers, as the company sought to learn from the best practices of contemporaries and apply them within their own business. It was during a tour of a printing company when second-generation owners Steve and Brian Kalina realized there was a better solution to the standard “suggestion box” many businesses use to encourage employee feedback. “While everybody who puts out a suggestion box has extremely good intentions, sometimes the suggestions are so far outside of their areas of expertise that it becomes very difficult to respond to them in an efficient and effective manner,” McGillivray says.

Steve and Brian were so impressed with the printing company’s solution, that they eventually brought nearly all of Dynamic’s employees through the facility. When Dynamic embarked on its own CI program, it split the company’s two buildings — one dedicated to molding (Ramsey, Minnesota) and one to moldmaking (Coon Rapids, Minnesota) — into six teams per building, including the aforementioned Team Motörhead — with competitions between the teams (at one point the contests were between buildings but now are mostly within the individual sites).

These days there’s a draft process each year where team members are selected over pizza and drinks, but initially to keep things simple, teams were composed of departments and suggested changes were restricted to their own day-to-day tasks. That wrinkle has since evolved.

“If it’s something you can put in place on your own with very little time and effort ... just do it.”

“As we’ve matured as an organization,” McGillivray says, “we all understand that when someone’s trying to make a suggestion, it’s for the betterment of everybody. Not because we don’t think you’re doing a good job, but because we think this will be helpful to all of us.”

Weekly meetings helped the company keep tabs on the changes that had been suggested and completed, and eventually, a new term for quick fixes was developed: “Just Do Its.” More complex proposed changes might require a large investment in time and money, with a team leader making a presentation to a manager and undertaking a formal project, but other changes are more straightforward. “If it’s something you can put in place on your own with very little time and effort,” McGillivray says, “as long as the rest of the group agrees that it’s a good change: just do it.”

Well over 90% of Dynamic’s business in molding and moldmaking is derived from the medical market. Photo Credit: Dynamic Group

Over time, the teams became more empowered, and the vast majority of the alterations made by Dynamic fell into this category. “Honestly, it’s shocking how many gigantic changes you can make without the need to involve higher level management,” McGillivray says, “especially when you’re talking about things like 5S.”

Among the most impactful changes to come out of the CI program was shifting secondary operations from beside the press to their own dedicated room. This space had additional lighting, racks for incoming/outgoing work-in-progress, and all the necessary tools, parts and instructions. “None of that was done with any management influence or participation,” McGillivray says. “They just did it on their own. The work and the efficiency continue to grow.”

To date, McGillivray only has one regret involving the program. “I wish we would have started putting little neon-orange dots at the location of a change or improvement,” McGillivray says. “Our company would be covered in them — they would be everywhere.”

Code Orange

Dynamic’s Code system of companywide alerts came out of a tour of a diesel engine remanufacturer. That company had struggled with scrap and rework, and instituted the program to not just address an issue but to find and eliminate its cause. “People were never really looking at how often they were having this problem and why — never getting to the root cause,” McGillivray says. “So, they were continually having high levels of rework and doing some of the same rework over and over.” The diesel engine company adopted the Code system Dynamic uses today, with issues addressed immediately, regardless of impact on other projects. “It was a giant commitment for them,” McGillivray says, “and it made their productivity go down for several weeks, but very quickly they started seeing less rework.”

Dynamic took the same approach and saw similar results. “We have a very, very good handle on the sources and causes of scrap, and we attack them extremely systematically,” McGillivray says. “Our team also understands that when there is scrap or rework needed, it’s almost never because someone did something wrong. It’s because the system wasn’t strong enough to prevent an easy human mistake from causing the problem.”

“We realized a lot of our scrap and rework was the result of incomplete training.”

The various codes that Dynamic has adopted over the years include: Code Black (notified by a customer that they believe something sent to them doesn’t meet spec). Here, if there truly was an issue, Dynamic finds the cause and eliminates the potential for a repeat offense. If there actually wasn’t a mistake, the company strives to get on the same page with the customer about what constitutes a good vs. bad part. Code Purples are instances where the company didn’t necessarily fail to satisfy specifications, but it might have not met expectations. Dynamic’s favorite? Code Green. “That’s when a customer says great job,” McGillivray says, and the alert broadcasts over the speakers. “Code Green, it says, and everybody goes, ‘Oh good, customers like us.’”

Dynamic has 20 injection molding machines, most in the 30- to 150-ton range, with one 400-ton press, molding roughly 600,000 parts/month over three shifts five days/week. Photo Credit: Dynamic Group

Over the years and through an analysis of the various codes, Dynamic determined the root cause at the base of many other root causes: incomplete training. As do many molders, the company often deploys contractors for simpler tasks around the plant, transitioning these people into longer term operator roles if they prove adept, with their numbers ebbing and flowing as orders do. To help these and other individuals succeed and reduce the number of Code Oranges and Blacks, Dynamic employs a dedicated full-time trainer on all shifts to continue teaching new employees, while also updating the knowledge of existing employees.

“We realized a lot of our scrap and rework was the result of incomplete training,” McGillivray says. “We found that having someone who is gifted at helping people learn quickly and designing educational programs would have a giant return. As a result, we’ve seen our first-pass yield go up dramatically, and the proportion of rework do down dramatically. We’ve also seen retention of employees go up, as well as the conversion of contractors to full-time employees.”

Partner Found, Company Founded

Back in 1977, working as a toolmaker, Dave Kalina simultaneously knew that he wanted to start his own moldmaking business and that he didn’t want to do so on his own, so he surveyed his colleagues for possible partners. “[Dave] looked around and said, ‘Who else is really, really good in this job,’” McGillivray says, “and I think my dad was honored to be asked, and personally, as my dad’s son, I think Dave made the right choice.”

Dynamic has a Class 7 cleanroom, as well as a Class 8 cleanroom tent, each housing two presses and assembly areas. Photo Credit: Dynamic Group

As Dave and Joe’s father, Peter McGillivray, found success in toolmaking, they wondered that if their customers were doing so well running the molds they make, could they possibly do so as well? In cases where mold changes were needed, they also saw how expensive the delays were that came from shipping tools back and forth to either coast where many of their medical customers were. Sampling tools in Minnesota on in-house presses would eliminate that issue, and Dynamic Engineering was created.

On a business trip to Switzerland to research wire EDMs, they were able to tour a highly successful moldmaker that had six molding machines for sampling. Impressed and motivated, the partners came back to Minnesota determined to invest in injection molding machines. They discovered there was a lot of local demand for quick-turn and prototype tooling and created Dyna-Plast in 1994 knowing that the rapid turnaround customers would place a high value on sampling, requiring a high number of samples annually. Presses used for these tools could also be used to sample the production tools for which Dynamic Engineering was known.

Dyna-Plast was set up as a separate company because the founders realized they might have an opportunity to get into bridge and short-run and/or production molding, and they didn’t want to scare Dynamic Engineering’s customers away by appearing to become competitors. McGillivray notes that the original business plan did not include a road map to get into molding, just an awareness that having good sampling capabilities would probably make getting into selling molded parts fairly easy. The company was also separate because successes as a quick-turn moldmaker required a very different approach from Dynamic Engineering’s; it called for its own culture, brand and processes.

Overall, the quick-turn business was successful, but there were times that working with startup medical device companies proved challenging. “Our customers were very happy with the lead times and prices on the tooling,” McGillivray says, “but sometimes those companies never made it to production or it just took way longer than anticipated.”

In 2008, Dynamic decided to stop marketing the fast turn and prototyping part of the business. “It just wasn’t making money,” McGillivray says. “We continued to inadvertently fund small startup medical device companies through the engineering phase.” At this point, the present-day Dynamic Group was born, with Dyna-Plast and Dynamic Engineering combined into one business, albeit in two distinct buildings 10 miles apart.

In 2016, the day-to-day operations of Dynamic Group were transferred to the second generation: Joe McGillivray along with Brian and Steve Kalina. As that group stepped up, McGillivray says the challenge has been shifting from a small- to a medium-sized business and one where the owner is at the center, making all the big decisions, to hiring and supporting individuals to run departments and steer the business.

“I think that’s one of the biggest challenges for any small family-owned business: transitioning from an owner-operator being at the center of everything to learning how to find, hire and support fantastic managers that can run departments or parts of your business better than you ever could,” McGillivray says. “That’s the big transition we’re going through as an organization, and I am as a person as well.”

Covering nearly 17,000 ft2, Dynamic’s toolmaking operation has 35 employees and builds roughly 125 molds/year, using flexible shifts to cover 24 hr/day five days/week. Photo Credit: PT

Related Content

Use Cavity Pressure Measurement to Simplify GMP-Compliant Medical Molding

Cavity-pressure monitoring describes precisely what’s taking place inside the mold, providing a transparent view of the conditions under which a part is created and ensuring conformance with GMP and ISO 13485 in medical injection molding.

Read More3D Printed Spine Implants Made From PEEK Now in Production

Medical device manufacturer Curiteva is producing two families of spinal implants using a proprietary process for 3D printing porous polyether ether ketone (PEEK).

Read MoreIndustrial Resin Recycling Diversifies by Looking Beyond Automotive

Recycler equips for new business in medical, housewares and carpeting.

Read MoreCustom Molder Pivots When States Squelch Thriving Single-Use Bottle Business

Currier Plastics had a major stake in small hotel amenity bottles until state legislators banned them. Here’s how Currier adapted to that challenge.

Read MoreRead Next

Achieving Continuous Improvement Using SMED Programs

A good SMED quick changeover program can help optimize financial performance by converting non-value-add time into value-add time.

Read MoreHow Serious Is Freudenberg Medical About Lean Manufacturing?

One employee I met there helped his daughter undertake a Kaizen event on her closet.

Read MoreWhat It Takes (And Doesn’t Take) To Be a Medical Molder

Medical molders absolutely must have a clean room and be ISO certified, right? ‘Wrong,’ says Extreme Molding’s Joanne Moon.

Read More