Plastics, Electronics and the Environment: How New Global Regulations Affect Materials Choices

Increasing concerns about the impact of chemicals on health and the environment are being translated into strict legislation that may have significant impact on the use and disposal of plastics, particularly those used in electrical and electronic equipment.

Increasing concerns about the impact of chemicals on health and the environment are being translated into strict legislation that may have significant impact on the use and disposal of plastics, particularly those used in electrical and electronic equipment. OEMs and their molders and extruders must take a careful look at current and upcoming legislation around the world to ensure compliance.

Fortunately, innovative plastics are currently available as alternatives to those that are facing regulatory restrictions. These new alternatives can contribute additional benefits such as eliminating costly secondary operations. Through such innovations, plastics can help protect the environment and improve profitability for manufacturers.

Concerns about limited natural resources, pollution and waste, and clean water and air have become global in scope. As a result, environmental regulations are being enacted in Europe and Asia, as well as the U.S., that are changing the design, manufacture, use, and disposal of products in many industries. This is the case in industries such as automotive and packaging, but nowhere is it more acute than in electronics, where design cycles and product lifespans are short, unit builds are high, and manufacturers design, produce, and sell globally. Plastics processors that make components for electrical/electronic equipment need to understand the current and potential impact of these regulations so that they can select the best materials to enable compliance and offer a competitive advantage.

E/E regs’ global impact

Expanding volume, short lifecycles, and an ever-growing waste stream: these are three key reasons why environmental regulations have targeted electronics and electrical equipment. New types and improved models of electronic devices, telecommunications equipment, and electrical appliances are flooding the marketplace. Cell phones, computers, DVD players, televisions, GPS finders . . . with the speed at which new technology is developed, last year’s model is frequently discarded in favor of the latest features. The impact on waste disposal resources—both landfills and incinerators—is a practical concern for many governments.

The European Union and Japanese government have taken the legislative lead in this area, although China, the U.S., and other countries are also tightening their requirements. Europe’s village-centric culture, incineration-based waste infrastructure, and political concern for the environment have helped drive strict environmental legislation. Because E/E equipment is such a global market, these requirements do not only affect the domestic manufacturer: any OEM or component or sub-assembly producer that supplies electronics or electrical equipment to the EU countries must comply. The practical implication is that unless companies choose to design and produce distinct product lines for different geographies, environmental legislation has global impact.

Because plastics are so diverse and are used in so many industries and types of products, they are affected by many regulations across the world. Four regulatory areas that are especially important to plastics processors are air quality, end-of-life waste, toxic substances, and fire safety.

Improving air quality

Several regulations in Europe, the U.S., and Japan govern atmospheric emissions. Directive 2001/81/EC of the European Union sets upper limits for each EU member state for total emissions by 2010 of four atmospheric pollutants–sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxide, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and ammonia—that cause acid rain, smog, and other harmful air and water pollution.

The 1990 Clean Air Act is a U.S. federal law under which the Environmental Protection Agency sets limits on how much of a pollutant can be in the air anywhere in the U.S. Japan’s Law for the Protection of Ozone regulates the production and consumption of specified substances such as chlorofluorocarbons and promotes the rationalization of their use to protect the ozone layer.

These regulations can affect plastics product manufacturers, causing companies to eliminate or reduce the emissions from painting or finishing operations or even replace processes like hand-laid fiber-reinforced plastic (FRP) composites, which produce significant styrene emissions. GE and other plastics companies can offer technical solutions such as alternatives to high-solvent painting operations.

Use of pigmented resins instead of paint can reduce VOC emissions and lower production costs while providing new design options. As an example, GE’s Visualfx resins offer a wide range of colors and special effects such as pearl, glitter, metallic, and many others without the need for paints or coatings.

Another processing technology that can eliminate either paint or printing is in-mold decoration (IMD). In this process a thin film of a plastic such as GE’s Lexan polycarbonate is preformed to match the part shape and then inserted into the injection mold. The tool is then filled as normal, creating a part with permanently bonded surface decoration. The IMD film can either be preprinted with custom graphics or extruded with metallic or other custom looks. Either method offers an attractive alternative to paint and allows easy customization. What’s more, the print can be applied on the underside or second surface of the film, where it is not vulnerable to mechanical abrasion or chemical attack.

Similarly, powder coating, which does not produce VOCs, may be suitable to replace high-solvent paints on plastics or metal parts. Certain engineering resins, like grades of GE’s Noryl GTX (nylon/PPO), can withstand the high-temperature ovens used to cure the powder coating. Grades of these high-temperature resistant resins are also available with conductive filler, which eliminates the need to apply a conductive primer coating in order to permit electrostatic topcoating (powder or liquid). Fewer steps in the total finishing process saves time and money as well as protecting the environment.

Structural panels made of thermoset FRP composites can be replaced with thermoplastic alternatives. Multi-layer coextruded sheet for thermoforming offers weatherability plus colors or other aesthetic effects and may provide economic advantages by automating what would otherwise be a labor-intensive process like hand-laid FRP or other composites. In addition, aesthetic structural or thermoplastic sheets eliminate the emissions and health hazards from styrene and acetone used to process composites and gel coats and clean up afterward.

End-of-life waste

Because electronic devices and electrical appliances are so prevalent and product turnover is so high, they produce a large amount of waste. Several laws aim to reduce this waste by mandating recycling and encouraging manufacturers to improve material choices and create better designs.

In response to the concern for hazardous waste in discarded electronic or electrical devices, and a growth rate for E/E equipment waste projected to be three to five times that of average municipal waste, the European Union created the Waste Electrical and Electronics Equipment (WEEE) Directive 2002/96/EC. This directive requires all OEMs and component and sub-assembly producers providing products to the EU to take responsibility for the E/E products they manufacture at the end of their useful life—including collection, recovery, and treatment. Producers must accept financial responsibility for these activities.

In addition, E/E producers must meet targets for recovery and recycling—50% to 75% by weight, depending on category of equipment. Manufacturers must remove printed circuit boards, batteries, CRTs, LCDs, and external cables from end-of-life E/E equipment. They must remove any plastic containing brominated flame retardants and treat it separately.

The WEEE Directive was issued by the European Parliament in January 2003. It directs member governments to implement the Directive in national legislation by August 2004, to develop collection systems and procedures for E/E producers so they can comply with end-of-life responsibilities by August 2005, to comply with recycle and recovery targets by January 2007, and to establish new reuse/recycle targets by December 2008.

The largest practical implication is that for all products sold or supplied to the EU market after August 13, 2005, the costs for collection, treatment, recovery, and environmentally sound disposal of WEEE are to be paid by producers. The legislative intent of this directive is that when producers are responsible for their products at the end of their useful life, they will make more environmentally conscious decisions. These decisions may involve redesign, material consolidation or simplification, and reuse and recyclability.

Other legislation affecting waste includes the following:

- Japan’s Household Appliance Recycling Law, implemented in April 2001, targets TV sets, air conditioners, washing machines, and refrigerators. These are now returned to manufacturers for recycling. As a result, OEMs are now trying to create appliances that are easier and cheaper to dismantle.

- The EU Packaging Waste Directive aims to reduce product packaging that contributes to waste streams.

- EU Directive 2000/53/EC on end-of-life vehicles stipulates that vehicle manufacturers and their material and component suppliers must try to reduce use of hazardous substances when de signing vehicles. They must design and produce vehicles that facilitate dismantling, reuse, recovery, and recycling. In addition, they must ensure that components of vehicles placed on the market after July 1, 2003 do not contain mercury, hexavalent chromium, cadmium, or lead. Lastly, the directive requires automobile manufacturers to recover 85% of vehicle (by weight) at end of life, of which 80% must be reused or recycled. These requirements are to increase to 95% and 85% respectively by 2015.

In view of the growing trend toward producer responsibility, different approaches to design and material selection are being employed by progressive OEMs. First, reduction of secondary operations such as painting and coating can simplify recycling. Some countries require coatings to be removed before landfilling or incineration, or coated parts to be separated for special handling. Replacing coatings with resins that have molded-in color or that produce a high-gloss finish, like GE’s new Lexan EXL resin, can eliminate this issue.

Recycling is a possibility for OEMs that wish to reuse portions of the plastic components that they collect. This is currently being done to a small degree in the auto industry. But for electronics it is often more expensive to manufacture a high-performance resin that meets UL safety standards with incorporation of post-consumer recycled material. However, GE and other companies are continuing to investigate technology that can solve this difficult environmental problem. One example is the recent introduction by GE of Valox iQ and Xenoy iQ resins. These grades use PBT manufactured using a patented process in which 85% of the chemicals inputs are reclaimed from post-consu mer PET bottles and film. E/E connectors are one potential application for Valox iQ resin.

Reducing toxic substances

Lead and other heavy metals, as well as certain brominated compounds, have been shown to accumulate in the environment. The EU’s ELV Directive for Automobiles and Restriction of Hazardous Substances (RoHS) Directive for E/E form the baseline by which similar restrictions are being developed by other nations.

The proper name for RoHS is Directive 2002/95/EC, “The Restriction of the Use of Certain Hazardous Substances in Electrical and Electronic Equipment.” RoHS applies to the following substances for electronic equipment and electrical appliances: lead, mercury, cadmium, hexavalent chromium, PBB (polybrominated biphenyls), and some PBDEs (polybrominated diphenyl ethers). The RoHS directive applies to products, components, or sub-assemblies for E/E equipment in the EU after July 1, 2006.

China has enacted a law similar to RoHS, called “Administration on the Control of Pollution Caused by Electronic Information Products.” This law, which also took effect this July, calls for a separate catalogue that will define which product classes are covered. Unlike RoHS, it requires that the names and contents of toxic substances be indicated on the products.

For the plastics industry the proscribed chemicals that are most relevant are lead, cadmium, and PBDEs. The main types of PBDEs are octa-bromine, penta-bromine, and deca-bromine. Currently, the first two are re stricted by both EU and China RoHS directives. To comply with this legislation, plastics and other materials that contain these substances must be replaced with alternatives that do not contain the chemical. As of September 2005, deca-bromine was exempted from the EU RoHS restrictions, but the ruling is currently under review.

RoHS sets maximum allowable concentrations for “homogeneous materials” of 0.01% for cadmium and 0.1% for the other substances. This definition can get complex when considering circuit boards and other electronic components. But plastics themselves are considered homogenous materials.

WEEE and RoHS are separate directives with different timelines, but their effect on the selection and use of plastics is intertwined. Several technologies are available to assist processors to produce parts that comply with the WEEE and RoHS directives.

- Colorants: GE and other companies have reformulated their resins to achieve high-chroma red, orange, and yellow colors without heavy metals.

- Flame retardants: The WEEE directive requires all materials containing bromine to be marked and treated separately at the end of life. In addition, the RoHS directive restricts the use of materials containing all PBDEs except deca-bromine. In order to simplify recovery and recycling at end of life, many OEMs are consolidating materials and limiting choices to plastic products that meet the performance requirements of the application without using brominated or chlorinated flame retardants. GE Plastics offers a number of these, including several grades of Cycoloy PC/ABS, Lexan PC, Ultem polyetherimide, Noryl PPO alloys, and LNP specialty compounds

- Flexible vinyl: Flexible PVC wire coatings have traditionally used lead-based heat stabilizers. Although lead-free PVC wire formulations are available today, many electronics companies are interested in other alternatives that are both lead-free and do not contain other halogens, such as chlorine—an integral component of PVC resin. One alternative is GE’s new Flexible Noryl resin for wire coatings. It is a UL 1581-approved, flame-resistant material for appliance wiring.

The electronics market is actually moving faster than the legislation requires. For example, many electronics companies have decided to reduce use of halogen-containing plastics in their products voluntarily. Both the EU and China RoHS-type directives exempt deca-bromine their restrictions and neither addresses chlorine. Despite this, many electronics OEMs have publicly declared their intention to reduce or eliminate PVC and other halogen-containing materials such as deca-bromine as part of their corporate environmental vision and commitment.

Increasing fire safety

Another trend in E/E standards involves fire safety. Although there are many chemical additives that allow plastics to meet increased fire-safety standards, some like PBDE’s are facing increased restrictions.

Another important activity is the harmonization of regional safety requirements into a single global standard. This is being done through the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC), whose global representation includes standards-setting organizations (UL, ISO, and others), fire-safety professionals, and manufacturers. The IEC has been working for several years to combine and consolidate six different E/E fire-safety standards into one global standard through Technical Committee 108 (TC-108). A general agreement has been reached to include performance requirements related to external flame risk. Previous standards were primarily based on the risk of fire related to a spark or short circuit within the equipment, but may be updated to include external ignition from a candle or other source.

If these provisions are enacted, many additional plastic components used in electronics, such as speakers and keyboards, could require higher levels of FR performance. Although certain formulations of materials like Noryl, Cycoloy, Lexan, and Cycolac ABS resins meet these increased requirements without halogenated flame retardants, there is concern in the industry about the possible economic impact of moving to higher-performing materials.

Christine Murner is the ecomagination leader and director of agency programs at GE’s Plastic Business in Pittsfield, Mass. Before joining the company in 1992, she worked for Pfizer Pharmaceuticals. Murner has held various technical marketing positions at GE Plastics, including a focus on the building/construction industry in China.

Related Content

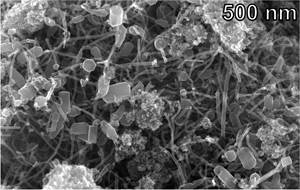

Research Suggests Path From Waste Plastics to High Value Composites

Flash joule heating could enable upcycling of waste plastic to carbon nanomaterials.

Read MoreRead Next

People 4.0 – How to Get Buy-In from Your Staff for Industry 4.0 Systems

Implementing a production monitoring system as the foundation of a ‘smart factory’ is about integrating people with new technology as much as it is about integrating machines and computers. Here are tips from a company that has gone through the process.

Read MoreSee Recyclers Close the Loop on Trade Show Production Scrap at NPE2024

A collaboration between show organizer PLASTICS, recycler CPR and size reduction experts WEIMA and Conair recovered and recycled all production scrap at NPE2024.

Read MoreLead the Conversation, Change the Conversation

Coverage of single-use plastics can be both misleading and demoralizing. Here are 10 tips for changing the perception of the plastics industry at your company and in your community.

Read More