Tracing the History of Polymeric Materials: Part 31, The Conclusion

Let’s close this lengthy series with some personal anecdotes.

Nearly three years ago I received an email from a reader asking if I knew the story about John Wesley Hyatt’s development of Celluloid. I wrote back that not only did Hyatt discover the chemistry behind Celluloid, he developed the machinery for forming the material — a process that today we call injection molding. That reader then suggested I write about that, and we have been doing so ever since November 2020.

We have covered a lot of ground during that time, 31 articles in all, and I am going to close with a couple of stories — one personal and the other historical — that involve two of the materials we mentioned in the first installment of the series.

We certainly have not covered everything that exists in the world of polymers. One item we have neglected that comes to mind is the fascinating history of the development of ABS, with its evolution from the use of nitrile rubber to butadiene rubber, the ongoing advances in the technology used to incorporate that rubber into the polymer matrix, and the breakthroughs in the 1980s with improved purity and color pioneered at Dow by my esteemed colleague, John Bozzelli. I am sure there are others.

But, hopefully, we have provided an informative, interesting and even entertaining account of the history of polymer development and the personalities that contributed.

Exploding Ping Pong Balls

The first story involves my attempt to identify the material used to make a common recreational product. Working in the lab, we would often get people coming in from the production floor inquiring about the composition of this material or that material. In the early days, the only pieces of equipment we had in the lab were a melt flow rate tester and a moisture analyzer. So to determine composition, we did what many in the industry have learned to do, identify a material using the sense of smell.

An observant person working on the manufacturing floor quickly learns that certain materials, when heated, give off distinctive odors. When presented with an unknown material, heating the material with a torch and then smelling the off gasses at least enables us to identify the overall polymer family. It can also lead to some interesting injuries which the Human Resources Department probably frowns upon. But back then we did not yet have a Human Resources Department, so we got away with a lot.

Hopefully, we have provided an informative, interesting and even entertaining account of the history of polymer development and the personalities that contributed.

On this particular day, the object of interest was a ping pong ball. We dutifully exposed the part to a flame, expecting that we would be able to extinguish the resulting fire and smell the vapors arising from the ruins. Much to everyone’s surprise, the object burned instantaneously and completely, leaving nothing behind but a trace of ash. But the explosive nature of the reaction was unmistakable; the material was cellulose nitrate.

It illustrated why this material never became the commercial option for billiard balls. It also brought to life stories about the movie house fires in the early 1900s when film was made from cellulose nitrate, and the origin of the nickname “mother-in-law silk” for the fabric made from this polymer that caused people to suddenly lose a layer of clothing when they came too close to a flame source.

The second story goes back to the 19th century and is worth considering as we go through our current political climate. In the mid-1850s, the country was becoming increasingly polarized over the issue of slavery and the U.S. Congress was the focal point of this debate. The passing of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in May of 1854 had prompted the formation of the Republican Party and galvanized the abolitionist movement. It gave individual territories entering the Union as states the right to decide whether they would enter as free states or slave states, with Kansas being a focal point of conflict over the question during this time. While Kansas did ultimately join the Union as a free state early in 1861, violence and armed conflict over the issue raged for years prior to that event.

A Cane Mutiny

The conflict was reflected in the U.S. Congress, where disagreements over the issue boiled over on May 22, 1856, when a Democratic member of the House of Representatives from South Carolina, Preston Brooks, entered the Senate chamber and beat Charles Sumner, the abolitionist Republican senator from Massachusetts, with his walking cane. Sumner’s injuries were so severe that he was unable to serve in his role as Massachusetts senator for almost three years.

During this time, Massachusetts chose not to elect someone else to take Sumner’s seat, actually reelecting him in 1856 and leaving his seat in the Senate chamber empty as a visual reminder of the event. Brooks was arrested for assault, tried in a D.C. court and fined $300, but served no prison time. He resigned from his seat on July 15 of that year, but was reelected in a special election on August 1, having achieved substantial support from his constituency due to the assault on his colleague. He was then elected to a new term during the regularly scheduled elections later that year.

Ironically, Preston died of an upper respiratory infection before the new term began in 1857. But in a magnanimous gesture before the end of the 1856 term, he gave a speech in which he stated he would be satisfied with Kansas entering the union as a free state if that was the decision of those writing the state constitution. It was a speech that earned him some unlikely support among abolitionists and the enmity of his pro-slavery supporters. Sumner returned to his seat in the Senate in 1859, but suffered chronic pain and what we would today identify as post-traumatic stress disorder for the rest of his life, while his detractors mocked him for exaggerating the extent of his injuries. He lived until 1874, still serving in the Senate when he died.

The parallels between that period in our history and today are notable. The emotionally charged ideological disagreements, the invective flying between the different sides, the compartmentalized media fanning the flames and even the physical assaults all have modern counterparts. But the historical fact that likely catches the attention of a chronicler of the plastics industry is the material from which Brooks’s cane was made. It was a relatively new material known as gutta percha, a thermoplastic derived from a tree of the same name.

About the Author: Michael Sepe is an independent materials and processing consultant based in Sedona, Ariz., with clients throughout North America, Europe and Asia. He has more than 45 years of experience in the plastics industry and assists clients with material selection, designing for manufacturability, process optimization, troubleshooting and failure analysis. Contact: (928) 203-0408 • mike@thematerialanalyst.com

Related Content

A Systematic Approach to Process Development

The path to a no-baby-sitting injection molding process is paved with data and can be found by following certain steps.

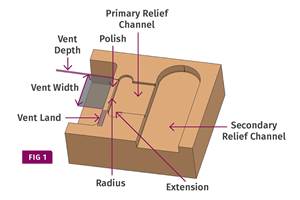

Read MoreBack to Basics on Mold Venting (Part 2: Shape, Dimensions, Details)

Here’s how to get the most out of your stationary mold vents.

Read MoreBack to Basics on Mold Venting (Part 1)

Here’s what you need to know to improve the quality of your parts and to protect your molds.

Read MoreFundamentals of Polyethylene – Part 6: PE Performance

Don’t assume you know everything there is to know about PE because it’s been around so long. Here is yet another example of how the performance of PE is influenced by molecular weight and density.

Read MoreRead Next

Tracing the History of Polymeric Materials -- Part 29: Polyurethane

This material family has unparalleled versatility, not only in terms of the forms the material can take, but in the different ways in which it can be processed.

Read MoreTracing the History of Polymeric Materials, Part 27: Liquid-Crystal Polymers

Liquid-crystal polymers debuted in the mid-1980s, but the history of the chemistry associated with this class of materials actually starts a century earlier.

Read MoreTracing the History of Polymeric Materials -- Part 30: Polyurethane

In the world of polymers, polyurethane chemistry is probably the most versatile. This a resulted in a wide range of products made from these materials and given the industry the flexibility to respond to the progressive march of regulatory concerns.

Read More

.jpg;width=70;height=70;mode=crop)