Don’t Get Caught in the Flash-and-Shorts Chase

Injection molding’s most common defects can have inverse correlation, where correcting one causes the other, leading to the “chase.”

The technology available today for injection molding is very impressive, providing molders with tools to increase part complexity and improve the quality and accuracy of production. Yet even with these advances there are still two obstacles that molders have to deal with.

Atempting to “fix” short shots (above) can result in producing flash (below) and vice versa. A better approach is to start with an optimized process and seek the root cause of the initial problem—shorts or flash—and resolve that issue.

Throughout my career, I have had the opportunity to visit many different injection molding facilities spanning multiple industries, and the one thing that they all share are their top scrap reasons—flash and short shots. These are by far the most common defects in injection molding. One reason for this is that in most cases they are direct opposites of one another.

Many of the actions we take to eliminate shorts can result in flash and vice versa. These actions can be made via changes to the process, mold, or combination of the two.

If the machine was running good parts and suddenly is producing shorts, something changed in that process, and it must be identified to resolve the issue.

For example: Shorts can be caused by inadequate venting in the mold, and to help eliminate these shorts, we may need to increase the depth of existing vents or add more. However, it is possible that by doing so, the result could be excessive flash. Now that flash is present, we decide to resolve our new problem by compromising the process to increase material viscosity. This can be done by lowering the melt temperature, causing an injection-pressure increase. This increased pressure increases our Delta P—the difference between maximum pressure used vs. maximum pressure required—so that the pressure now exceeds the maximum available injection pressure of the machine, which results in—you guessed it—sporadic short shots due to being pressure limited. So we’re back to where we started.

So, as you can imagine, there can be a fine line between flash and shorts, and that fact can shrink our process window significantly. Our goal as a processor is to find that middle ground far enough away from either side so that normal process variation doesn’t result in either defect.

Flash’s Root Causes

Flash can have many different causes, but two of the most common are excess cavity pressure and mold damage. Cavity pressure can cause flash when it exceeds the available clamp force. Once the clamp force is exceeded by the cavity pressure, the mold can physically open, allowing plastic to escape the cavity-forming steel. Excess cavity pressure can have many causes of its own, including a blocked gate preventing some of the cavities from being filled. Mold damage can also allow for plastic to escape the cavity-forming steel by preventing the parting line from sealing properly.

Coming Up ‘Short’

Shorts or short shots are under-filled parts that are typically missing features due to lack of plastic. Sinks and under-packed parts can sometimes be related to shorts or can be an indication that shorts are starting. Shorts can be caused by a number of reasons, and it is critical to identify the root cause before trying to address them. Common causes include improper venting that prevents gasses from escaping so that plastic can’t flow into the cavity; or the nonreturn valve on the screw not closing properly and plastic flowing backwards as the machine injects. As I have stated in a previous column, understanding the why is critical to correcting the issue.

Finding the Root Cause, Avoiding the Chase

Keep in mind that both shorts and flash are symptoms of a deeper problem. We must understand what is causing the symptom before trying to fix it. For example, increasing shot size when shorts suddenly appear can result in flash, if the root cause isn’t understood before making the change. If the shorts are caused by debris stuck in the nonreturn valve, forcing it to remain open during injection, increasing your shot size may eliminate the shorts until the debris works free. Once the debris is freed from the nonreturn valve, and it is once again allowed to close properly, the extra shot size we added could cause the cavity pressure to exceed the clamping pressure and result in flashing the mold.

Just because you can make a few good-looking parts by reducing the hold pressure, that doesn’t mean that the process is robust enough to accommodate normal process variation in production.

In my experience flash and shorts are among the main problems that can start the “chase.” That refers to making process changes on a machine multiple times in reaction to the current defect. Example: A short is discovered and the machine operator informs the process technician of the issue. This busy technician stops what he or she is working on to come over to the machine and increases the hold pressure without doing any sort of root-cause investigation. The technician looks at a shot to verify the shorts are gone and tells the operator the parts are good to pack.

Let me be clear here and say that process changes should be the last thing we do to correct an issue. If the machine was running good parts and suddenly is producing shorts, something changed in that process, and it must be identified to resolve the issue. That said, we all get busy and pressure can push us towards the path of least resistance in order to move on to the next problem. We should always troubleshoot an issue and identify the root cause before making modifications, but that doesn’t always happen—it should, but it doesn’t.

Back to our example: A little time goes by and the operator starts seeing flash on the parts—that’s right, flash on the machine that was just producing shorts. It turns out that whatever was causing the shorts is sporadic and the additional hold pressure that was added is now causing the mold to flash. The operator gets a different technician, who notices that someone increased the hold pressure and now there is flash, so of course this technician lowers the hold pressure. No more flash, problem solved. What happens next? The sporadic issue that’s causing the shorts hits again and they return, forcing the operator to seek help again to address the shorts. This chase can go on for hours or even longer, depending on the skill level of the process team, the size of the overall process window, and the actual root cause.

When I think about this type of chase, as a processor, it does feel like something is working against you. I’ve been there. I can recall several shifts spent chasing a process early in my career … not knowing any better and being responsible for 12 aging machines with poorly designed molds and just trying to move on to the next firefight. In these cases, we bring this on ourselves to some extent, but it can take you off your game, especially if you’re trying to be in multiple places at the same time.

When it comes to troubleshooting flash and shorts, the first step is identifying which one is really the issue. Since they can be direct opposites of each other, it is key to know which defect is present at the optimal processing conditions. For example: Even though shorts are the issue we are currently seeing, flash could ultimately be what needs to be addressed. Flash could be preventing us from increasing our hold pressure to an optimal setting to compensate for normal process variation, which is resulting in short shots. So the issue we should be addressing is the flash at our optimal process setting and not the shorts that are currently present. The above example is important to remember during process development, as well. Just because you can make a few good-looking parts by reducing the hold pressure, that doesn’t mean that the process is robust enough to accommodate normal process variation in production. If we can develop a process that can prevent normal process variation from causing defects, troubleshooting becomes much more simplified and helps those process technicians make better decisions.

Finding the optimal process between flash and shorts will always be an obstacle for molders. I would also venture to say that they will continue to be the top scrap reasons for most molders. But how you approach problem solving will determine whether you chase these defects or will solve them.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Robert Gattshall has more than 22 years’ experience in the injection molding industry and holds multiple certifications in Scientific Injection Molding and the tools of Lean Six Sigma. Gattshall has developed several “Best-in-Class” Poka Yoke systems with third-party production and process monitoring such as Intouch Production Monitoring and RJG. He has held multiple management and engineering positions throughout the industry in automotive, medical, electrical and packaging production. Gattshall is also a member of the Plastics Industry Association’s Public Policy Committee. In January 2018, he joined IPL Plastics as process engineering manager. Contact: (262) 909-5648; rgattshall@gmail.com.

Related Content

Where and How to Vent Injection Molds: Part 3

Questioning several “rules of thumb” about venting injection molds.

Read MoreFundamentals of Polyethylene – Part 6: PE Performance

Don’t assume you know everything there is to know about PE because it’s been around so long. Here is yet another example of how the performance of PE is influenced by molecular weight and density.

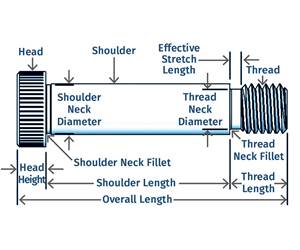

Read MoreWhy Shoulder Bolts Are Too Important to Ignore (Part 1)

These humble but essential fasteners used in injection molds are known by various names and used for a number of purposes.

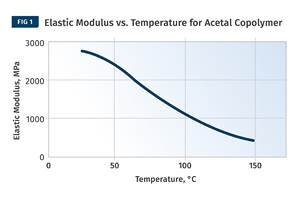

Read MoreThe Effects of Time on Polymers

Last month we briefly discussed the influence of temperature on the mechanical properties of polymers and reviewed some of the structural considerations that govern these effects.

Read MoreRead Next

INJECTION MOLDING: Scientific Molding Gone Wrong

Sometimes molders get trained in Scientific Molding only to revert to their old way of doing things as soon problems pop up.

Read MoreUnderstanding—and Using—Decompression to Your Advantage

Decompression—aka suckback—is a very important setting on an injection molding machine. On today’s machines, molders typically get the option to set decompression before and after screw rotation/recovery. Are they using this feature to their advantage?

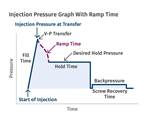

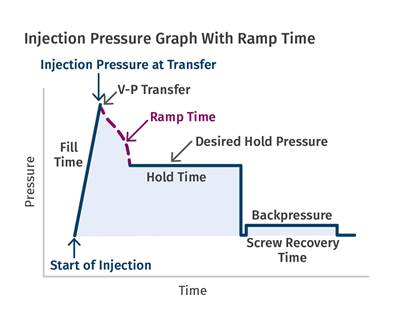

Read MoreV-to-P Ramp Time and Over-Travel

Many injection machines use ramp time to control the transition from injection pressure to hold pressure and reduce over-travel. Do you know how to set yours?

Read More