In-Line Compounding of Long-Glass/PP Gains Strength in Automotive Molding

Another approach to long-fiber thermoplastic (LFT) molding is gaining credibility for producing a range of structural and semi-structural automotive parts. It is called direct LFT processing, and is already widely practiced in Europe.

The most common method of molding polypropylene reinforced with long-glass fiber is to use precompounded 0.5-in.-long pellets. However, another approach to long-fiber thermoplastic (LFT) molding is gaining credibility for producing a range of structural and semi-structural automotive parts. Called direct LFT processing, and already widely practiced in Europe, it allows molders to self-compound long-glass PP in-line with injection or compression molding of parts like seat bases, front-end assemblies, bumper beams, under-body plates, door surrounds, and interior consoles.

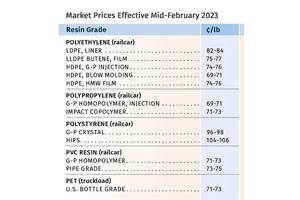

Direct LFT lets molders use PP base resin (priced around 40¢/lb) and raw glass fiber (around 75¢/lb) rather than ready-to-use LFT pellets costing about $1.25/lb (with a typical 40% glass content). Those who license or sell direct-LFT technology claim material cost savings are up to 60%, while final part cost can be up to 40% lower than with injection molded pellets. Even greater savings are available to molders of GMT sheet or special LFT pellets with glass lengths of 1 to 1.5 in.

“Our economics are better because we eliminate the middleman,” states Dr. John Busch, director of business development at Composite Products Inc. (CPI) in Winona, Minn. CPI practices and licenses technology for its “direct-feed thermoplastic” (DFT) process for compression molding.

Besides improved economics, advocates of direct-LFT methods further argue that their approach better retains the length and integrity of glass fiber and improves wet-out and distribution, all of which translates into moldings with superior mechanical properties (e.g., impact strength) and surface appearance.

Suppliers of precompounded LFT pellets reject the view that their products can be readily displaced in automotive applications. They are LNP Engineering Plastics, Exton, Pa.; Ticona LLC, Summit, N.J.; RTP Co., Winona, Minn.; and StaMax LLC, Toledo, Ohio (a joint venture of Owens Corning and DSM Engineering Plastics). Indeed, they say new versions of their compounds, including “super-concentrates” of 75% glass in PP pellets, offer major cost savings of their own. In addition, they claim that ready-to-use pellets remove risk factors and high investment costs involved in self-compounding. “Many automotive molders are reluctant to become formulators or incur the hidden costs that role brings,” says Maria Grosser, market manager at StaMax LLC.

New automotive successes

CPI’s system has been in commercial use for a decade. It uses a single-screw extruder to mix resin and additives and then feed the melt to a second extruder where the glass is blended in. The fibers are preheated before entering the extruder to open the bundles and ensure good wet-out. Also, the second extruder’s screw is designed to minimize glass breakage.

The glass/resin mix is extruded as thick preforms of controlled weight between 2 and 30 lb. Hot preforms are robotically placed in compression or transfer molds. CPI achieves cycle times of 40 to 70 sec. Molding is synchronized with compounding throughput rates up to about 2400 lb/hr.

In a representative 12-lb part, Busch claims average DFT materials cost 70% less than GMT and 50% less than precompounded pellets. He estimates final part-cost savings at 20-50%. In-line compounding incurs added equipment costs, but Busch argues that they can be amortized at modest annual production volumes (e.g. 30,000 to 50,000 units).

A recent success for DFT is the door surrounds for current-model DaimlerChrysler soft-top Jeep Wranglers. Now CPI has broadened its role in that platform by molding a front roof header for these vehicles. CPI showed that its parts matched the previously used structure of steel and polyurethane SRIM in mechanical (e.g., wind-load) properties as well as appearance, while beating all available alternatives on cost.

“This part reveals the structural and aesthetic capabilities, plus cost-effectiveness, of our system,” Busch claims. He attributes the success to excellent wet-out and distribution of glass in the matrix. For instance, data on the soft-top header shows variance in glass content measured at eight points on the part is less than 1% (41.15% to 40.34%) for a nominal 40%-glass formulation. Also, CPI’s data show parts’ tensile, flexural, and impact values modestly exceed those for injection molded PP/glass compounds.

Not only has CPI itself won new automotive molding business, but in late July, Tier One auto-parts supplier Decoma International in Concord, Ont., decided to license CPI’s DFT process. Decoma chose this route after a two-year evaluation of alternative options for processing glass-reinforced PP.

In previous years, CPI put higher priority on licensing its process to others than on its own custom molding business. A license was issued to Swedish automaker Volvo, whose S70 platform includes an integrated front-end assembly in which long-glass/PP replaces a 20-piece steel weldment. Volvo’s licensing rights are exercised now by one of its contract molders, but its pending programs are said to include LFT skid and underbody plates and noise control applications.

Meanwhile, other early CPI licenses have lapsed. Busch ascribes this to restructuring in the global automotive business. Now, CPI has shifted strategy, repositioning itself as an automotive parts molder with expertise in direct LFT. In non-automotive applications, CPI is molding structural appearance parts for office-furniture leader Herman Miller of Zeeland, Mich.

More in-line LFT methods

Another system for in-line compounding and compression molding long glass fibers is offered by C.A. Lawton Co. in Green Bay, Wis. Its Long Fiber Deposition-Compression Molding process draws on plastication and robotic-transfer technology acquired from Kannegiesser in Germany.

This equipment, as well as compression presses, are sold by Lawton in various configurations, including one that utilizes LFT pellet compounds. The latter approach is used by Johnson Controls and other molders in the U.S. and Europe to make polypropylene structural automotive parts.

“The most intense current interest among U.S. users is focused on in-line systems,” remarks Dan Bellerud, Lawton’s director of marketing and sales. Depending on part complexity and production volume, Bellerud estimates savings of 20-25% for in-line LFT compounding and molding when matched against even the most efficient (i.e., super-concentrate) versions of premade LFT pellets.

Bellerud says Lawton’s equipment ensures good wet-out and dispersion and retains glass length of 1 to 1.5 in. after compression molding. Direct LFT equipment also offers the molder formulating freedom not achieved with GMT sheet or ready-made LFT pellets. Other benefits claimed for direct LFT methods are a single heat history, lower energy use, and reduced equipment wear. Ability to easily reuse scrap is another advantage over GMT molding.

Meanwhile, two injection machinery suppliers are developing in-line LFT systems in which a twin-screw extruder blends resin and long glass and feeds the mix directly to a molding machine. One is being co-developed by Husky Injection Molding Systems Ltd., Bolton, Ont., and Coperion Werner & Pfleiderer of Ramsey, N.J.

A second variant, which is termed Injection Molding Compounding (IMC), is commercially producing automotive PP moldings in Europe. The system yokes a Hermann Berstorff twin-screw compounder with an injection machine from sister firm Krauss-Maffei, both of which have U.S. offices in Florence, Ky. They plan to show an IMC system at the K 2001 show producing a tailgate using glass-filled ABS.

And that’s not all. As we reported last month, Berstorff has introduced a twin-screw system that allows molders to compound their own GMT sheet.

Related Content

The Fundamentals of Polyethylene – Part 1: The Basics

You would think we’d know all there is to know about a material that was commercialized 80 years ago. Not so for polyethylene. Let’s start by brushing up on the basics.

Read MoreFundamentals of Polyethylene – Part 3: Field Failures

Polyethylene parts can fail when an inappropriate density is selected. Let’s look at some examples and examine what happened and why.

Read MoreFungi Makes Meal of Polypropylene

University of Sydney researchers identify two strains of fungi that can biodegrade hard to recycle plastics like PP.

Read MoreFirst Quarter Looks Mostly Flat for Resin Prices

Temporary upward blips don't indicate any sustained movement in the near term.

Read MoreRead Next

See Recyclers Close the Loop on Trade Show Production Scrap at NPE2024

A collaboration between show organizer PLASTICS, recycler CPR and size reduction experts WEIMA and Conair recovered and recycled all production scrap at NPE2024.

Read MoreFor PLASTICS' CEO Seaholm, NPE to Shine Light on Sustainability Successes

With advocacy, communication and sustainability as three main pillars, Seaholm leads a trade association to NPE that ‘is more active today than we have ever been.’

Read More