Mold Designers Put the Web to Work

The internet is redefining the tool-design process. Some mold designers are finding that using the Web to manage a tool project can shorten lead times, cut costs, and make sure vital data get to all participants in a project.

Suppose your next big molding project depends on delivering a tool design fast. The deadline looms. What do you do? Your first move is to access a website housing an online “virtual work space” on the internet, where you can obtain up-to-the-minute revisions of the OEM’s part design. (No time to wait for mail or even overnight courier service.) On this site you also collect specs from the resin supplier on a new formulation that you can plug into your mold-simulation program.

Next, you accelerate the tool-design process by collecting complete CAD drawings of mold bases, hot runners, and other mold components from suppliers’ websites, so you don’t waste time drawing any mold elements unnecessarily.

Suppose you want to confer with the OEM and moldmaker about the cost impact of different tool-design approaches. There’s no time to send drawings or to translate your models for viewing on a different CAD system. Instead, you call the parties together in the virtual work space, where each can examine and manipulate your CAD models of the tool using only their desktop web browsers.

As the clock ticks, you e-mail your project partner in Tokyo, who will continue working on the mold design after you close up shop for the night and then hand it back to you for the finishing touches when you return in the morning.

All this is not a fantasy of the future. They are capabilities that a number of molders and moldmakers are using today. New web-based means of communicating tool-design information are helping eliminate delays and trimming the chances for data to be lost in transit or mistakes to be made in implementing the latest revisions to a project. Even the occurrence of last-minute changes can be reduced by using the new internet tools to maximize communication among all parties from the start of a project. “A lot more of our tool design is going through the web. Using the web for design is becoming more vital,” says John O’Kelly, chief engineer at PM Mold in Schaumburg, Ill.

Real-world examples of how the internet is changing tool design can be found on the websites of suppliers of mold bases, hot runners, and other mold components—the likes of D-M-E, Gunther, Hasco, Husky, Incoe, Mold-Masters, PCS, and Progressive Components, to name a few—which have brought do-it-yourself capabilities to their web portals. Designers get access to entire catalogues of mold components and can assemble entire hot halves or mold bases (in some cases with the help of software “wizards”) and then download those subassemblies to their own CAD systems. At the same time, designers can get a cost quote and place an order.

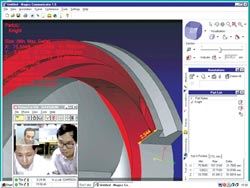

Delcam, a CAD/CAM software vendor, offers a collaborative workspace via its web portal, where users in distant locations can interact in a virtual conference setting. There they can look at the same 3D CAD design and turn, split, and mark it up in real time, while discussing the project via web cam and microphones. All records of the meeting—notes, suggestions, design chan ges, and assigned tasks—can be maintained on the portal.

Iberomoldes, a Portuguese mold maker, and Centimfe, a Portuguese moldmaking technology center, are establishing a global network of product and tool designers that can move development of a CAD design continuously from shop to shop in different time zones to keep a project going around the clock.

Injection molder Harbec Plastics Inc. in Ontario, N.Y., says it has saved from 20% to 50% in design-development time for various projects by using an online collaboration website, OneSpace, hosted by CoCreate Software Inc. “Use of the site allows us to do complex jobs quickly and with a greatly reduced chance that rework will be needed. Mold rework can easily cost up to $100,000,” says Harbec CEO Bob Bechtold. Because all parties to a project gather in the virtual space to discuss the model, these online sessions have cut some typical six- to 10-week jobs by 50%, says Bechtold. “We don’t do simple parts,” he adds.

It’s all about speed

The means of communicating tool-design information between mold designer, moldmaker, molder, and end user are becoming as important as the content of the design itself. Conventional means of interaction and information exchange between these parties—such as phone calls, e-mail, faxes, overnight courier services, and even face-to-face meetings—are being re-evaluated as development cycles are compressed to speed new products to market.

“Product life cycles are getting shorter and shorter, so molders need to get tools built faster. Shaving lead times is becoming critical to success and survival,” says Greg Foss, tooling engineer at Miniature Tool and Die, a molder and moldmaker in Charlton, Mass.

“Time definitely is money, John O’Kelly, chief engineer at PM Mold concurs. “Even though we could deliver a mold design to a customer by overnight courier, then get on a phone and talk about a project, that may not be enough to get the job. It may only take a day for the information to get there and a day for it to return, but even that amount of transit time could mean the difference in a molder being competitive enough.”

“The lead time for producing a tool including a CAD model varies from tool to tool, but it is often in the order of 10 to 12 weeks. When lead times are analyzed, it becomes evident that much of the time is consumed by the moldmaker waiting for vital data files to be approved and come back into his shop. The real production work of the moldmaker takes considerably less time,” says Stuart Watson, director of CAD product development at Delcam’s headquarters in the U.K. He adds that quoted lead times for mold models are often inflated by up to 40% to account for sudden design changes requested by the customer, the rework required, loss of information in transit, mistakes, and miscommunication between participants in the project.

Moldmakers say sending design data by e-mail is fast, but many CAD files are too large to be handled conveniently by e-mail. In addition, differences in the type of CAD format used by a mold builder and client can cause big delays. Designs could be corrupted during translation between CAD formats or when different CAD systems are used to mesh the same tool model for mold-filling simulation and analysis. “A mold designer with the capacity to handle a job may not get the nod for the work if the CAD packages used by the parties are not the same,” says Keith Leary, general manager of mold manufacturing at UFE Inc. in Stillwater, Minn.

Importing mold elements

All these issues are at the core of a burgeoning movement to move many aspects of mold design off the design engineer’s desktop and onto the internet. One of the most straightforward trends is to save time and effort by importing digital models of standard mold components and subassemblies directly into the tool designer’s CAD model of the mold. Component vendors’ online libraries grant users the freedom to conduct tool design when they want, not just during regular business hours.

For example, D-M-E’s website offers a CAD library of over 100,000 mold-base and component configurations in more than 85 different CAD formats. All these components can now be configured by the user online, then downloaded to be inserted into the mold assembly. “The components are available in numerous CAD formats,” says business development manager Larry Navarre. “Previously, when a customer wanted to configure a mold in CAD they would call customer service and work through them. Now they can log on and get it themselves.” D-M-E is adding collaboration capability to its site, which will promote a higher degree of interaction with online users.

Hasco’s website allows users to select mold bases, plates, and components such as hot-runner nozzles and manifolds. The free software can be downloaded onto a user’s computer or supplied on a CD. The system runs in CAD software or in Windows. It generates 3D solid models and bills of materials from the user-selected data.

Incoe is developing a 3D design library of entire hot-runner systems, but it currently offers mainly 2D surface CAD files. Users can select a nozzle type, length, pitch, and other information to customize the design.

Husky launched a file-exchange service in June 2000, through which users can log on to a secure space on Husky’s server and download 2D drawings of any component. After marking up the files with details on how the hot-runner system will be configured, the user downloads the file in any format. Users can also send the information to an internet File Transfer Protocol (FTP) site operated by Husky, from which it is easier to transfer bigger files.

Mold-Masters has offered an online hot-runner “configurator” for about five years. It includes 3D CAD models of its components, which can be downloaded in various formats. System configuration is aided by the Merlin Wizard. Also available is a history of a customer’s purchases. “Now customers can go online and look at all of their activity with us. They can look up part names, numbers, and previous design configurations and get a spare part quickly for an existing mold,” says director of information technology Dario Vettor. Mold-Masters is in the process of adding e-collaboration functionality to the site.

PCS last year made its complete catalog of mold-base and component drawings available online in over 90 file formats, including 3D solid models. The website’s software creates customized configurations based on a user-specified CAD format, says Terry Oplinger, general manager.

Mold-component suppliers em phasize that providing do-it-yourself design automation does not mean they abandon customers to their own devices. Most of these suppliers still conduct a design review with the customer, answer questions, and make suggestions on component selection.

Time to e-collaborate

Websites or “portals” can be configured as a central platform for communication and data transfer between all parties to a project. They provide an opportunity to share design models and data in real time, rather than merely transferring information back and forth. These portals can be managed by a mold builder, molder, resin supplier, or a third-party “application service provider,” or ASP.

“Through collaboration, engineering time is at least 10% shorter and you get quicker approval since the client can be online to offer its input early on,” says David Miller, engineering manager at Dynamic Tool and Design in Menomonee Falls, Wis., a designer of injection molds.

E-collaboration technology is offered by at least three suppliers of CAD mold-design software—Cimatron, Delcam, and ImpactXoft. Third-party e-collaboration portals that have been used by plastics designers include sites from CoCreate, NetVendor, and Web4.

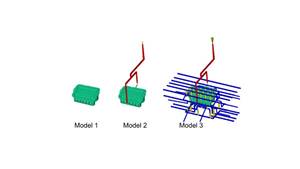

Another approach uses a single website linking mold designers from around the world. Data is downloaded in one location, marked up, and returned to the web portal. Another designer in a different time zone accesses the design, reads any instructions for the job, then continues the design work. Hence tool-design efforts continue around the clock.

Designers can also find websites offering services related to mold design. Moldflow provides a service that allows users to “rent” rather than purchase the firm’s Part Adviser mold-filling simulation on a pay-per-use basis by downloading a digital “key” from Moldflow’s website. Repair or translation of CAD models are offered as on-line services by firms such as C-Solutions, which help users correct problems with CAD designs converted from one CAD format to another. Also offering web-based CAD translation services are Autodesk, CADCAM-E.com, and STEP Tools.

Cimatron offers QuickConcept, web-enabled software for preliminary evaluation of tool designs that permits manipulation of CAD data in an e-collaboration environment without using a CAD system. Online design-review meetings let project members view and analyze a model concurrently. Participants can check the design for moldability and create several new iterations in a short time, while allowing control to shift between members.

Some of the websites can be accessed with only a desktop computer and a web browser, or by downloading the software. The software running the collaboration site usually supports conventional CAD viewing capabilities—such as rotate, zoom, and pan—plus the ability to bring in mold components created in other CAD formats and to maintain different versions of the design. The introduction of non-parametric geometries now allows features to be designed in a CAD environment with no associative history or permanent link to the original model. This enables features to be moved around a model without having to redraw it.

OneSpace, the collaboration site from CoCreate uses an example of this new type of free-form modeling and communication management. CoCreate developed Dynamic Modeling, a non-parametric 3D CAD format. This neutral format allows designs made in any 3D CAD package to be incorporated into the project design and viewed on the web portal. “Users have an ability to do ‘what-if’ variations on the design in a secure environment that can update the models fast,” says Irv Christy, U.S. director of marketing.

The data management portion of the software keeps history of typed conversation exchanges, references, and mark ups. It also has a model manager and product data management (PDM) features designed to keep involved parties up to date on the progress and scheduling of a project.

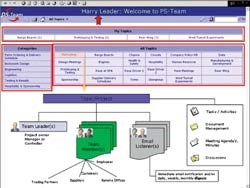

Similar capabilities are available from Delcam’s PS-Team software, NetVendor’s Embrace 5.0, ImpactXoft’s new IX Speed, and Web4’s eReview. In addition, SolidWorks offers a software tool called 3D Instant Website, which lets any SolidWorks CAD user put on its own website interactive 3D CAD models that can be viewed and manipulated by remote partners with just a web browser.

Design around the clock

Another way to shorten mold-design times involves linking together designers from around the world through a single web portal to work on a single project. Each designer, at an appointed time, downloads a file from a central location, works on the project, then uploads the CAD designs back to the portal, where the next designer, downloads the CAD file and starts his work. In this fashion the CAD design travels around the world on a non-stop 24-hr work cycle, says Joaquim Menezes, president of Centimfe, the Portuguese tooling technology center and a principal member of the Round-The-Clock (RtC) program.

RtC has completed about 20 mold programs so far. Centimfe is looking to broaden the network of designers and molders and to list each firm’s capabilities on the web.

Related Content

How to Achieve Simulation Success, Part 2: Material Characterization

Depending on whether or not your chosen material is in the simulation database — and sometimes even if it is — analysts will have some important choices to make and factors to be aware of. Learn them here.

Read MoreHow to Achieve Simulation Success, Part 1: Model Accuracy and Mesh Decisions

Molding simulation software is a powerful tool, but what you get out of it depends very much on your initial inputs. Follow these tips to create the most successful simulation possible.

Read MoreRead Next

For PLASTICS' CEO Seaholm, NPE to Shine Light on Sustainability Successes

With advocacy, communication and sustainability as three main pillars, Seaholm leads a trade association to NPE that ‘is more active today than we have ever been.’

Read MoreSee Recyclers Close the Loop on Trade Show Production Scrap at NPE2024

A collaboration between show organizer PLASTICS, recycler CPR and size reduction experts WEIMA and Conair recovered and recycled all production scrap at NPE2024.

Read More