Reworking Off-Spec Material? Add Some Science to the Mix

Reworking off-specification material and low-demand material is good for the compounder and good for the environment. Here’s how to make sure it’s good for the customer too.

Unwanted or off-spec material can often be “worked off” by mixing it in small amounts with “good” material. But what’s the right amount? (Photo: Matthew Naitove)

These days, when we’re trying to reduce our carbon footprint as much as possible, we want to try to recycle as much as we can, to not only improve profitability but also reduce the amount of waste we generate.

It’s a common practice for compounders to “rework” material that was slightly off-specification in terms of melt flow, ash content, etc., into good Class A material at some low percentage such that the overall product still stays within spec. That way, the compounder doesn’t have to sell off the off-spec material as scrap at a lower cost; valuable warehouse space is freed up; and the off-spec material isn’t landfilled.

When it’s “bad” material of some grade (let’s call it Grade Z), it’s easy to say, “The next time we run Grade Z again, we’ll just sprinkle some of the bad Grade Z material into the next good Grade Z material we run.” But what if you have some material (we’ll call it Grade Y) you only run once every three years? Or what if you have some material that you made for a customer trial they ended up not wanting, so now you’re stuck with 20,000 lb of compound in your warehouse that you’re most likely never going to run again?

That’s where you have to use a “non-like for like mixing” strategy to figure out the right amount of Grade Y to combine with Grade Z.

The first and hardest part to overcome is convincing the commercial team and upper management that this is acceptable. Remember, you are selling a specification, not a particular grade. When you sell a product to a customer, you are selling them a product with certain properties—tensile strength, melt flow, etc.—not simply Grade Z. If your Grade Z suddenly had double the melt flow or half its normal tensile strength, your customer would care a lot, and that is the most important aspect of this exercise.

When you sell a product to a customer, you are selling them a product with certain properties—tensile strength, melt flow, etc.—not simply ‘Grade Z.’

So how does one determine the right percentage of Grade Z to mix with Grade Y? There are a host of methods out there, each with their own pros and cons, but the method we’ll talk about today is using simple Euclidean distances, which any process engineer can accomplish with an Excel spreadsheet.

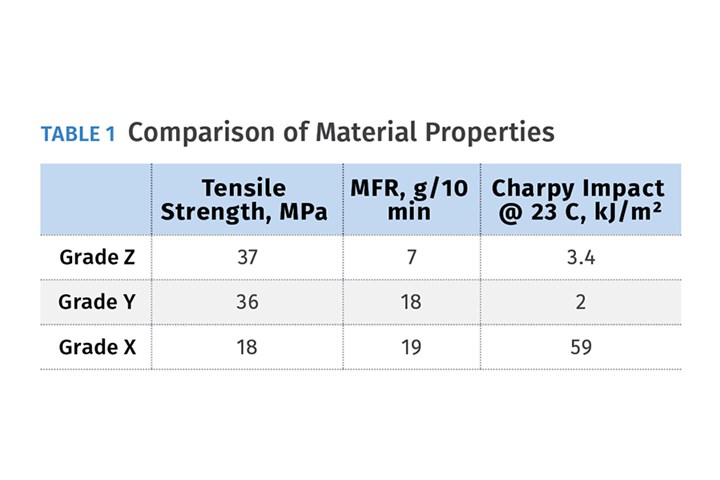

The first step is to arrange all of the grades you produce into a spreadsheet with grade names on the y-axis and properties on the x-axis (Table 1).

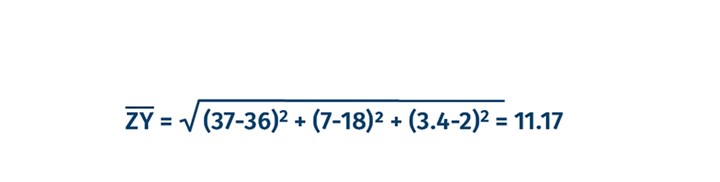

Then, once you have all your variables, you use simple Euclidean distances to calculate the distance, or how far off, one grade’s properties are from another.

For example, if you want to find out how far grade Z is from grade Y, calculate the following:

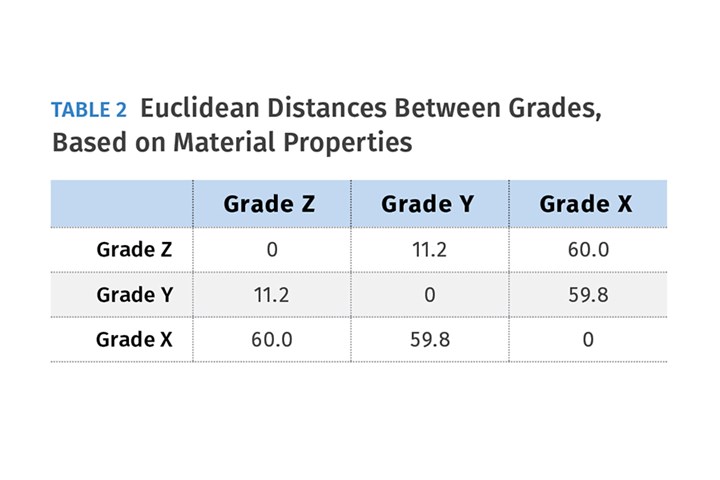

Once you do this for all the grades, you can assemble the data and compare and contrast (Table 2). If you remember reading the back of a Rand McNally Atlas with a table of the distances from one city to another, it will look just like that.

Notice that in terms of material properties, Grade Z and Grade Y are pretty similar, with scores of 11.2. But Grade Z and Grade Y are pretty far away from Grade X (scores of 59-60), so it’s probably not a good idea to mix those two—or if you do mix them, do so at a very low rate.

Now comes the fun part: What score represents how much you are allowed to put into what grade? If you have the benefit of experience—e.g., “We previously mixed this 30% talc grade into this 40% talc grade at 5% rework rate and it had this Euclidean distance score, then we should be able to mix two dissimilar grades with that Euclidean distance score at 5%”—then go for it.

If you don’t have that experience, this is where you’ll want to tread softly and ease into it. That is, dose in small dabbles with mixing together materials with the most similar properties. Start at at 1-3% rework rate, test for properties, then increase the loading gradually and test properties to see the effects.

Here are some final points:

• Usually, you’ll want to normalize the material property variables before comparison, so differently scaled properties don’t have an outsize effect on the similarity score.

• Another approach is to weight certain properties if they are more important to the customer. For example, if tensile strength is more important than density, then you can add “weights” in the formula to make the difference in tensile strength show more clearly than differences in density.

• You’ll want to review your table after you’re done to make sure you’re not adding two materials that have completely different qualitative properties. For example, you don’t want to add materials that don’t have scratch resistance to those that do, or you might not want to add glass-filled materials to those that are talc-filled, depending on the end customer.

• Euclidean distance is the most simple method of calculating similitude, but there are many more potentially accurate methods that can and should be explored.

• Some end products truly do have limitations on what specific raw material can be placed in them, so any potential non-like-for-like mixing opportunity should be reviewed with the customer and your compliance or legal team before implementing.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Bruce Spencer III is a professional engineer with many years of experience resolving engineering and production-related challenges related to extrusion. He is the owner of Valiant Phoenix Engineering in Dickinson, N.D. He has held various positions in the plastics industry over his career, including EHS, process engineering and production roles. Contact: info@valiantphoenix.com

Related Content

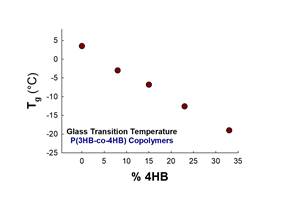

How to Extrusion Blow Mold PHA/PLA Blends

You need to pay attention to the inherent characteristics of biopolymers PHA/PLA materials when setting process parameters to realize better and more consistent outcomes.

Read MoreHow to Optimize Injection Molding of PHA and PHA/PLA Blends

Here are processing guidelines aimed at both getting the PHA resin into the process without degrading it, and reducing residence time at melt temperatures.

Read MoreInside the Florida Recycler Taking on NPE’s 100% Scrap Reuse Goal

Hundreds of tons of demonstration products will be created this week. Commercial Plastics Recycling is striving to recycle ALL of it.

Read MoreFilm Extrusion: Boost Mechanical Properties and Rate of Composting by Blending Amorphous PHA into PLA

A unique amorphous PHA has been shown to enhance the mechanical performance and accelerate the biodegradation of other compostable polymers PLA in blown film.

Read MoreRead Next

How to Ensure Reliable Feeder Performance When Handling PCR

Processors are being challenged to incorporate more recycled material into their products. Yet there are both economical and technical obstacles to achieving this objective—feeding among them. The design of your feeding equipment and the advantages that it will offer to your process will be more important than ever.

Read MoreSolvent-Based Recycling: Emerging Technology for Reclaiming & Purifying Polyolefins with Twin-Screw Extruders

Just now being applied commercially, solvent-based recycling turns colored polyolefin waste into clear, clean and even food-grade resin comparable to virgin—all while keeping the polymer structure intact. Specially engineered systems of tandem twin-screw or twin- and single-screw extruders can do the trick.

Read MoreHow and Where Twin-Screw Extruders Fit in Recycling

When utilized in a thoughtful way, the corotating intermeshing twin-screw extruder can transform recycled materials into value-added products and parts. Here’s what you need to know, and some real-world examples of the technology deployed for both post-industrial and post-consumer recycling.

Read More