Stop Black Specks!

Black specks in film or sheet–especially in light-colored or clear plastics–lead to scrap, unscheduled shutdowns, and dissatisfied customers.

Black specks in film or sheet–especially in light-colored or clear plastics–lead to scrap, unscheduled shutdowns, and dissatisfied customers. Specks can also cause holes in film or sheet when it’s later oriented or thermoformed.

There are two possible sources for black specks. Either you bought them with your raw material, or you manufactured them in your extrusion system by one of several mechanisms.

If specks appear in your product, first examine statistically representative samples of the raw material closely to be sure it isn’t the source. Raw material can also contain formulation defects known as “unmelts,” which char instead of melting, becoming a dark speck surrounded by a gel. Contaminants in raw material are uncommon these days, but not unheard of.

Specks or unmelts are more likely in off-spec or post-industrial recycled material. If you find contaminants in your raw material, confer with your supplier about remedies and increase your QC testing of incoming material.

If your raw material tests clean, then you’re making specks somewhere in your process. Small amounts of polymer are being overheated, exposed either to high temperatures for a short time or to moderately high temperatures for longer periods.

When an area of very high temperature occurs in the barrel, downstream plumbing, or die, it’s typically caused by a problem in the control system–a bad thermocouple, runaway heater band, or a relay stuck in the wrong position. Any material passing through the affected zone is potentially vulnerable to degradation.

Small amounts of resin can hang up and be exposed to normal process temperatures for abnormally long periods in a worn or pitted screw, barrel, or die, or in cracks in chrome plating. This material de grades over time, breaks loose with thermal cycling and the drag of polymer flow, and can make lots of black specks.

If you suspect an equipment problem, work with your maintenance department to identify and correct it. If you can eliminate control failures and worn equipment as causing the contamination, look next at system configuration, material characteristics, and process conditions.

Downstream plumbing

The screw and barrel rarely cause degradation, though vents or complex mixing or barrier sections may do so. Degradation usually arises downstream from the extruder–for example, in plumbing that forces abrupt changes in the polymer flow path or in components such as breaker plates, screen packs, static mixers, and melt pumps. These can have potential hang-up areas, like a too-abrupt taper into an adapter fitting.

Large or complex dies for film or sheet can also be the culprits if they contain low-flow areas where polymer can overheat. Your experience from past teardowns and inspections is the best indicator of whether degradation is developing in areas of slowed or stagnated flow. In blown film dies, it could be the point where each port is fed or where a splitter feeds a spiral. In cast film and sheet dies, trouble could arise where the shoulder starts to spread out or in the relaxation chamber at the land just before the die lips. Once identified, these areas should be given particular attention in future cleanings. They may require local use of higher temperatures plus chemical purging compounds.

Heat sensitivity

Heat tolerance of the polymer is also part of the picture. Heat-sensitive materials like PVC, ABS, and EVOH, or engineering resins like acetals, PC, nylon, or polyesters are more likely to degrade than heat-tolerant polyolefins. An extrusion system that processes LDPE with no problem might degrade heat-sensitive EVA in a matter of minutes. Make certain that residence times are not excessive and melt temperatures are below critical levels.

Also, consider throughput rate and shear sensitivity. Obviously, running too hot can lead to degradation. But on occasion, running too cold can, too. Forcing a cool material to flow can generate excessive shear energy and localized degradation in the screw’s flow channel.

Finally, consider the shutdown schedule and procedures. Stoppages and shutdowns for adjustments, die changes, or maintenance often extend residence time and cause material degradation. In a system operated five days a week, small amounts of residual material in the extrusion system acquire substantial heat history as the machine slowly cools and starts up again. So it’s common for a system on five-day operation to begin producing black specks only a few weeks after a complete teardown and cleaning.

When all else fails

In the real world, hardware design or operating conditions that are overstressing your material may not be immediately fixable. You may know that your material is susceptible to degradation, but changing resin isn’t an option without customer approval. Or you realize that weekend shutdowns are killing you, but you can’t justify going to 24/7 operation. In such predicaments, purging compounds can play an important role in managing contamination.

When problems result from hardware configuration or condition–die geometry, known hang-up areas, or even slightly worn screws–periodic use of a purging compound as preventive maintenance will attack degradation at an early stage and minimize troubles during startup. But remember, purging won’t eliminate the root cause of the degradation, so if your system is spewing out black specks at an intolerable rate, that’s not the best time to try a purging compound.

If weekend shutdowns are the cause of contamination, use a high-performance purging compound to remove heat-sensitive materials from the system Friday night–not after the fact on Monday–to avoid startup problems and unscheduled teardowns for cleaning.

Finally, use the right kind of purging compound for your situation. In general, mechanical purging compounds are best for color and material transitions in relatively small and simple systems. Chemical purging compounds are best for large or complex systems or for addressing pesky contamination issues like black specks.

Frank Van Haste is general manager of Novachem, a supplier of mechanical and chemical purging compounds in Bridgeport, Conn. He has focused on polymer processing systems since Novachem’s founding in 1989. He can be contacted at (800) 762-3984 or at frank.vanhaste@novachem.net.

Related Content

Why Are There No 'Universal' Screws for All Polymers?

There’s a simple answer: Because all plastics are not the same.

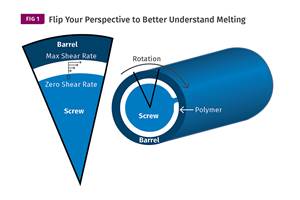

Read MoreUnderstanding Melting in Single-Screw Extruders

You can better visualize the melting process by “flipping” the observation point so the barrel appears to be turning clockwise around a stationary screw.

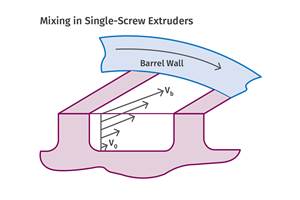

Read MoreSingle vs. Twin-Screw Extruders: Why Mixing is Different

There have been many attempts to provide twin-screw-like mixing in singles, but except at very limited outputs none have been adequate. The odds of future success are long due to the inherent differences in the equipment types.

Read MoreWhat to Know About Your Materials When Choosing a Feeder

Feeder performance is crucial to operating extrusion and compounding lines. And consistent, reliable feeding depends in large part on selecting a feeder compatible with the materials and additives you intend to process. Follow these tips to analyze your feeder requirements.

Read MoreRead Next

See Recyclers Close the Loop on Trade Show Production Scrap at NPE2024

A collaboration between show organizer PLASTICS, recycler CPR and size reduction experts WEIMA and Conair recovered and recycled all production scrap at NPE2024.

Read MoreFor PLASTICS' CEO Seaholm, NPE to Shine Light on Sustainability Successes

With advocacy, communication and sustainability as three main pillars, Seaholm leads a trade association to NPE that ‘is more active today than we have ever been.’

Read MoreBeyond Prototypes: 8 Ways the Plastics Industry Is Using 3D Printing

Plastics processors are finding applications for 3D printing around the plant and across the supply chain. Here are 8 examples to look for at NPE2024.

Read More