Why Non-Return Valves Leak

We all recognize that the non-return valve is a problem. The question is where is the research to figure out how to correct this so we have a better shot at making more consistent parts

One of the most important details in injection molding is the non-return valve or check ring. There are different types—the three-piece, four-piece, full-flow, ball check, etc.—and all are problematic. It would make my day if a group of molding company executives, quality directors, and six-sigma black belts witnessed how one of these non-return valves functions … not for 1 million shots but for 10,000. Then they’d realize that this mechanical device fouls up far more than a few shots in a million. Ask any molder if he would bet his money that the standard non-return or check valve would work perfectly for 10,000 shots.

We all recognize that the non-return valve is a problem. The question is where is the research to figure out how to correct this so we have a better shot at making more consistent parts. My definition of research is not someone sitting at a computer “simulating” flow through a valve. I want metal cut and tested and data recorded.

THE VALVE EXPERIMENT

If you feel these valves work fine, do an experiment. Measure the volume of the stroke for one of your parts. Take the shot size to cushion for stroke and use this equation:

Volume = pi times the barrel radius squared times the length of the stroke.

Now compare this volume to the volume of parts that come out of the mold. Weigh them and use the melt density of the plastic to calculate the volume needed to make the parts you weighed. (Melt density is not the same as the solid density seen on the data sheet. You’ll have to get the melt density from the material supplier.) My bet is that you will find that the shot volume is much larger than the volume calculated from the weight of your parts.

In addition, provide me an explanation of why 90% of all bridging in feed throats today is a solid melted ball of plastic. Feed throats running at 70 to 125 F are not hot enough to melt most plastics. There should be no melt in the rear feed flights of a screw.

That said, let’s revisit what we have and what technology might apply. Is there technology available that could help?

First of all, what qualifies as a “good” non-return valve? These are the basic functions of a non return valve:

1. To allow plastic to flow through it, not over it, during screw rotation to develop the required shot size for your part. There should be no dead spots for the plastic to accumulate or get hung up, and the flow path for the polymer should have minimum pressure drop and no shear stress due to sharp corners.

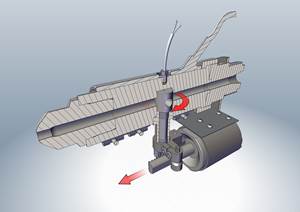

2. To provide a nearly perfect seal so that upon injection this valve slides shut and acts like the plunger in a syringe to push plastic forward into the sprue, runner, gate, and cavity—not allowing any melt to slip back into the screw during injection, pack, or hold. We want it to seal under pressures up to 40,000 or 50,000 or even 60,000 psi.

3. To seal instantly, or as quickly as possible, at the start of injection. Most of all, it should do so repeatably.

4. To do the above without excessive wear on the barrel inside diameter. It is possible for a non-return valve to work properly but still not hold a cushion due to wear on the inside diameter of the barrel.

5. To last at least six months to a year under normal use, understanding that some abrasive resins or filler will influence functional life.

We want the valve to seat or seal and not leak. Is it best to seal over a wide area or over a small area? Look at almost any container in your refrigerator, take the cap off, and analyze how the seal is made. These containers do a good job most of the time. Water, milk, or soda pop—there are relatively few failures.

The point is that a seal is made best over a small or narrow area, not a wide area. Take a look at the non-return valve, even a ball check, and you’ll see the sealing is over a relatively wide area. In fact it’s so wide that if you have a glass fiber, piece of dirt, or even a partially melted granule, you can have the injection pressure lifting the sliding ring or ball off its seat, creating a leak that will push molten polymer all the way to the feed throat after a few shots.

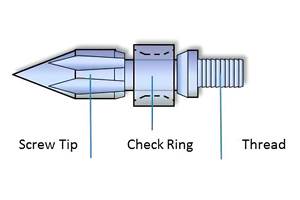

Decades ago, I had a student who pointed out that our typical non-return valve resembled a valve seating into the engine block of an internal combustion engine. It didn’t hit me right away, but he was right: Strip away the threaded shaft that screws into the plasticating screw and cut off the tapered tip and you have the exact same form and function of internal-combustion engine valves (see illustration on p. 13). They have to seat to keep air in the cylinder during the explosion of the fuel/air mixture to drive the piston down.

ENGINE BUILDERS FOUND A WAY

Engine folks found out 100 years ago that if you mate the angles of the valve seat, it does not hold air in the cylinder very well. To make it work they found you needed to step the angle, and the steps have to be steep.

Typical engines have three steps or angles, and racing engines can have five to seven. Granted, most of our non-return valves have a 1-2° difference in angle, but that is not enough. Check out Google or talk to your local car guy that does engine work. Bet they will get a chuckle if you tell them how we do it.

In plastics as well as in internal-combustion engines, the valve has to seat over a small area, period. The questions are what angle is best and where should it go—on the seat or the ring? Our industry is the third largest manufacturing sector in the U.S. and we need more and better fundamental research.

Let me close with a point about safety. If you work on a non-return valve or screw, make sure that after final assembly there is clearance between the screw tip and end cap when the screw is bottomed.

Related Content

Got Streaks or Black Specs? Here’s How to Find and Fix Them

Determining the source of streaking or contamination in your molded parts is a critical step in perfecting your purging procedures ultimately saving you time and money.

Read MoreA Guide to Ultrasonic Welding Controls

Ultrasonic welding today is a sophisticated process that offers numerous features for precise control. Choosing from among all these options can be daunting; but this guide will help you make sense of your control features so you can approach your next welding project with the confidence of getting good results.

Read MoreKnow Your Options in Injection Machine Nozzles

Improvements in nozzle design in recent years overcome some of the limitations of previous filter, mixing, and shut-off nozzles.

Read MoreFive Quick Steps Toward Better Blending

Rising costs of resins and additives, along with higher demands for quality and use of regrind, place a premium on proficient blending. Here are some steps to get you there.

Read MoreRead Next

See Recyclers Close the Loop on Trade Show Production Scrap at NPE2024

A collaboration between show organizer PLASTICS, recycler CPR and size reduction experts WEIMA and Conair recovered and recycled all production scrap at NPE2024.

Read MoreLead the Conversation, Change the Conversation

Coverage of single-use plastics can be both misleading and demoralizing. Here are 10 tips for changing the perception of the plastics industry at your company and in your community.

Read MoreMaking the Circular Economy a Reality

Driven by brand owner demands and new worldwide legislation, the entire supply chain is working toward the shift to circularity, with some evidence the circular economy has already begun.

Read More

.jpg;width=70;height=70;mode=crop)