Injection molded metals have their say at medical event

Injection molded plastics have long found new applications by replacing metals; but these days it is often injection molded metals that are replacing metal components formed by casting, machining, or other processes.

Engel hosted a West Coast Medical Day event last week at its Corona, Calif. technical center, and while plastics dominated the agenda, the Austrian injection molding machine and automation supplier invited speakers from a metal molding customer and a new technology partner who gave attendees a glimpse into another side of injection molding.

Liquidmetal Technologies, Rancho Santa Margarita, Calif., only has two licensees for its amorphous metals, but the fact that one of them is Apple has garnered the company a great deal of attention. Paul Hauck, VP worldwide sales and support for Liquidmetal is new to his position (five weeks in when he presented in Corona), but not the industry, bringing 27 years of experience in metal injection molding.

As it pushes to broaden commercialization of its moldable alloy, which was initially discovered by NASA during research in the 1960s, Liquidmetal has sought partners, reaching an agreement with Engel in 2010 to supply machines especially outfitted to mold Liquidmetal, and a deal in 2011 with Materion Corp., to produce the specialty alloy.

Hauck laid out Liquidmetal’s intellectual property position—the company has 58 U.S. patents with more than 50 pending—and then got into the unique characteristics of the material and its process, infusing his presentation with knowing commentary of the limits and strengths of traditional metal injection molding.

At various points, Hauck compared the precision of Liquidmetal against die casting, MIM, investment casting, and machining, saying the molded alloy could hold tolerances within ±.1, putting it on par with machining and ahead of the others. “Liquidmetal shines in areas with very high part complexity,” Hauck said.

One slide compared the strength (in MPa), hardness, strength-to-weight ratio, and elasticity of Liquidmetal Alloy versus magnesium, aluminum, titanium, and stainless steel, with its alloy—a mix of zirconium, nickel, beryllium, calcium, and titanium— besting those metals, often by quite a bit. Hauck noted that the individual components of the alloy have very high melting temperatures, but combined together in the alloy, they melt at 720 C with a density of 6g/cm3.

A key differentiator from traditional MIM: Liquidmetal molding produces near net shape parts (shrinkage of only .2%), where MIM components can shrink as much as 20% and require the secondary processes of debinding and sintering. Post-molding Hauk said all a Liquidmetal part requires is degating.

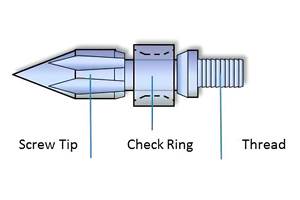

In terms of the molding machine, Hauck showed a Schwertberg-made Engel eMotion, that instead of a traditional reciprocating screw injection system, features an induction heating system, which draws a vacuum and warms to 700 C, with a plunger to feed the melt. The material, which comes in ingots versus the powder/binder mix of MIM, is automatically fed via a modified loading section.

Liquidmetal is currently undertaking ISO 10993 parts 4, 5, 10, and 11 biocompatibility testing, a necessary step for greater medical adoption, and Hauck noted that the preliminary results “were very good.” Finished Liquidmetal parts are corrosion resistant and non-magnetic, with a very fine surface finish. “If you have a polished tool,” Hauck said, “you’re going to have a polished part.”

Hauck said the machines can create parts as heavy as 80g, with a maximum shot size of 100g. If individual parts weigh 5g or less, tools of 32 or 64 cavities are possible. From a design standpoint, Hauck said components should have radii, and given that shrink rate of .2%, some draft is required. Wall thickness can range from 1 to 4 mm, but Hauck cautioned that if designs go thicker, the finished components risk crystallization in the thicker sections, negating the inherent strength of the amorphous structure. It is that feature which makes Liquidmetal particularly compelling.

“Liquidmetal has the name ‘metallic glass’,” Hauck said, “but that’s deceiving. Technically it is true but the finished material is still quite flexible.” To prove this, Hauck showed videos of Liquidmetal test plaques being flexed mechanically but returning to their original shape, while other metals were permanently deformed.

Oregon-based MIM molder expands sales into China

Hauck’s presentation was followed by former MIM colleague, John O’Donnell, medical market manager and senior applications engineer at Kinetics Climax, an Oregon based metal injection molding company that has standardized on Engel presses since its inception in the 1980s as Injection Molded Metal Products.

Today, Kinetics has 400 employees operating 25 hybrid and hydraulic injection molding machines 24/7 to produce 60 million parts annually.

That output, and the current repeatability of the MIM process, reflect the technology’s maturation from its birth in the 1970s. “Even though MIM is a 35-year-old technology,” O’Donnell said, “it’s really just starting to grow because it’s taken about half that time to perfect it and make it the robust process it is today.”

For his part, Hauck estimated that MIM is growing anywhere from 15-30% per year and now constitutes a $5 billion industry.

That growth is felt acutely at Kinetics, which O’Donnell noted is “bursting at the seams” and weighing an expansion. From a sales standpoint, it has already increased its reach, recently opening a sales office in Shanghai from which its able to sell Chinese customers MIM parts molded in the U.S.

Whether it’s MIM, Liquidmetal, machining or something else, Hauck noted that savvy engineers will listen to the part’s design to find the right process for its fabrication. “With any given part,” Hauck said, “it seems like it always wants to find its way back to the right process. [Liquidmetal] is not trying to chase applications that are the wrong fit.”

Related Content

Got Streaks or Black Specs? Here’s How to Find and Fix Them

Determining the source of streaking or contamination in your molded parts is a critical step in perfecting your purging procedures ultimately saving you time and money.

Read MoreHot Runners: How to Maintain Heaters, Thermocouples, and Controls

I conclude this three-part examination of real-world problems and solutions involving hot runners by focusing on heaters, thermocouples, and controls. Part 3 of 3.

Read MoreUsing Data to Pinpoint Cosmetic Defect Causes in Injection Molded Parts

Taking a step back and identifying the root cause of a cosmetic flaw can help molders focus on what corrective actions need to be taken.

Read MoreProcess Monitoring or Production Monitoring—Why Not Both?

Molders looking to both monitor an injection molding process effectively and manage production can definitely do both with tools available today, but the question is how best to tackle these twin challenges.

Read MoreRead Next

Making the Circular Economy a Reality

Driven by brand owner demands and new worldwide legislation, the entire supply chain is working toward the shift to circularity, with some evidence the circular economy has already begun.

Read MoreBeyond Prototypes: 8 Ways the Plastics Industry Is Using 3D Printing

Plastics processors are finding applications for 3D printing around the plant and across the supply chain. Here are 8 examples to look for at NPE2024.

Read MoreFor PLASTICS' CEO Seaholm, NPE to Shine Light on Sustainability Successes

With advocacy, communication and sustainability as three main pillars, Seaholm leads a trade association to NPE that ‘is more active today than we have ever been.’

Read More