What Blow Molders Say About All-Electric Machines

They are well established in Europe, but molders in North America are just beginning to come around to all-electrics’ improved performance, maintenance, cleanliness, and—yes— energy efficiency. Here’s first-hand testimony, from the U.S. and abroad.

North American bottle blow molders are sometimes described by machinery vendors as a fairly conservative lot, content to stick with their familiar hydraulic shuttles and injection-blow presses. Meanwhile, after more than 15 years on the market, more efficient all-electric alternatives have become quite popular in Europe and are growing in Asia and elsewhere. But there are signs in the sales figures that U.S. blow molders are finally warming up to all-electric machines.

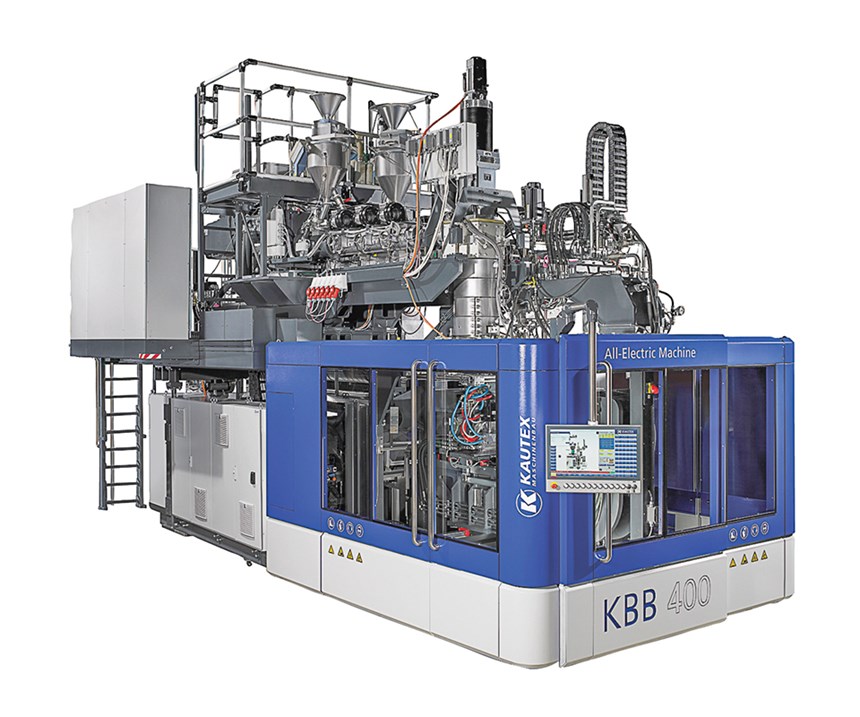

For at least one domestic bottle molder, that did not require a big leap of faith. “We’ve had tremendous success with all-electric injection molding machines, and that’s all we will buy from now on,” says John Ciampi, manager of maintenance and facilities at Currier Plastics in Auburn, N.Y. So it was logical for Currier to look for similar efficiency improvements in all-electric blow molding. Its first step in that direction was to purchase in 2015 a new- generation KBB electric shuttle machine from Kautex that was introduced to the world at the K 2013 show in Dusseldorf (see Sept. ’13 show preview and Feb. ’14 post-show report). Its experience with that press over the past 18 months has convinced Currier to focus on all-electrics going forward, according to Steve Crawford, blow molding engineering manager.

TURNING THE TIDE

Currier Plastics is something of a pioneer in all-electrics on these shores. Interviews with the three main sources of all-electric extrusion blow and injection-blow machinery in North America— Bekum, Kautex, and Milacron—indicate that roughly half a dozen such machines are in place on this continent and another small handful are shipping or on order.

Gary Carr, v.p. of sales for Bekum America Corporation, Williamston, Mich., says most domestic extrusion blow molders appear to be satisfied with traditional hydraulic machines: “They’re proven and reliable, their maintenance is known, and they are more affordable,” he notes, citing around 15% cost premium for all-electrics. Bekum’s modular platform allows use of hydraulics or electric servos on the same basic press. “We have quoted all-electric versions for special projects, such as clean-room medical molding, or unique requirements better suited to an electric machine.”

Bekum has offered all-electric shuttles since at least K 2001, but has not pushed them very hard in North America until recently. At NPE2015 in Orlando, Fla., the company introduced its first electric machine, the EBlow 607D, that uses domestic components such as servo motors, actuators, and controls. After exhibiting at the show (see March ’15 NPE preview), Bekum ran the machine at its plant for 2000 hr to conduct an engineering assessment. This month, the machine is going to a U.S. customer’s plant to initiate commercial production. That customer’s motivation, according to Carr, is partly a need for additional capacity, partly curiosity to test something new, and partly out of a desire to form a business partnership with Bekum to participate in the latest technology developments. This customer has several HyBlow 607 hydraulic versions of the same machine, so it will provide a direct comparison on performance after some months of operation.

Carr says energy savings, though significant, are not a compelling reason for U.S. molders to invest in all-electric machines. The real benefit, he says, is greater accuracy and repeatability. He is looking to see this verified in production with the first domesti- cally equipped EBlow 609D. European molders, he says, were more receptive to new technology because electric utility costs are much higher there. He esti- mates that over half of shuttle machine sales for Bekum in Europe are all-electric.

Carr also notes that all-electric shuttles are becoming more attractive thanks to a larger range of available sizes. “Up to now, they have been mainly smaller machines, but we are bringing out a larger model at K 2016.” He is referring to the EBlow 37, and electric machine for canisters or jerrycans of 10 and 35 liters (see Sept. ’16 show preview and photo, p. 50).

Also bringing out larger all-electric models at K 2016 is Kautex, with its KBB200 and KBB400 models for jerrycans. Chuck Flammer, v.p. of sales for North America at Kautex Machines, Inc., North Branch, N.J., agrees that it has been “slow going” up to now for electric machines in North America. He says that in recent years, bottle makers have had ample capacity and consequently have been averse to capital spending, except for those few that were expanding capacity.

Flammer agrees that higher electric costs have helped gain acceptance of electric presses in Europe, where the KBB series are its largest-selling packaging machines. Kautex no longer even offers its smaller shuttles with hydraulic drive, and its mid-size KLS hydraulic models actually cost more than comparable KBB electrics. He says more than 25 KBB machines have been ordered globally, up from two or three in the first year, 2013.

He sees growing sales in China, too. “The Chinese know their costs to the penny. They are choosing all-electrics for energy savings and for faster cycles.”

Here, too, Flammer senses a change in the weather. He says two electric shuttles are running in North America, three more are shipping, and two more are on order, with two more orders in the works. Flammer expects that next year’s electric machine sales will double, as bigger companies get into the act with 10-machine orders. Although energy cost is 7-10% of bottle cost, the main advantage in the domestic market is accuracy and repeatability. “You can make the process window very narrow with all-electrics. The first shot of a new run is just like the last shot of the previous run.” He also notes that dry cycles are as much as 50% faster with the new electric series, and overall cycles are at least 10% faster.

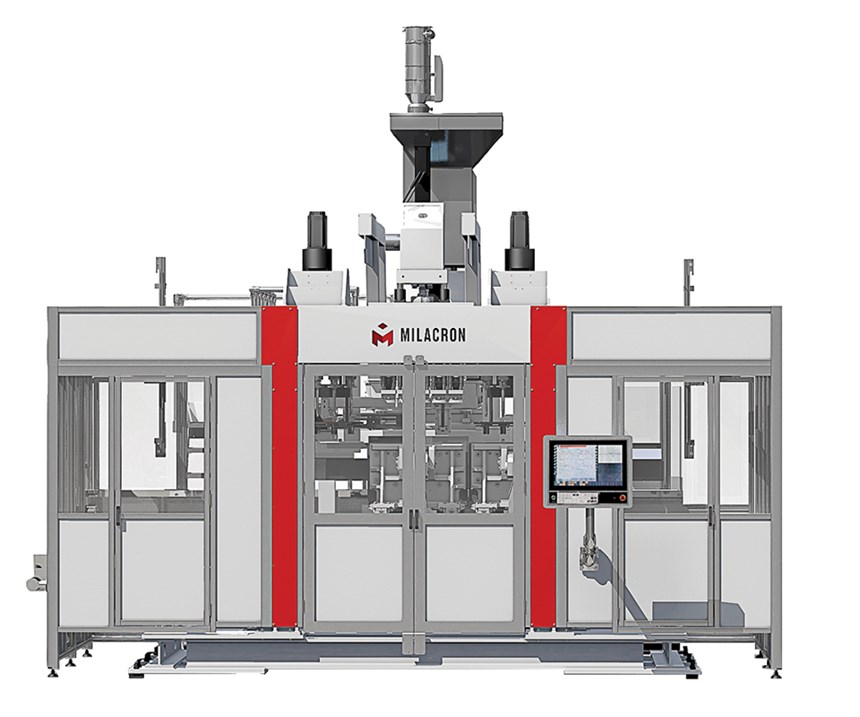

Milacron Plastics Technologies, Cincinnati, tells much the same story. It launched its first all-electric shuttle in 2007 and its third-generation M-Series debuted last month at K 2016 (see this month’s Keeping Up section). In Europe, around 80% of its shuttle machine sales are now all-electric. “Sales have gone up every year. Quite a number of customers will buy only all-electric,” says Colin Taylor, v.p. of global sales for Milacron’s Uniloy brand. “Also in Asia and South Africa, we have customers who now buy exclusively electric machines.”

It has been harder to overcome the conservative nature of the domestic market, he notes, even though most machines sold here in the last 10 to 15 years have been hybrids with hydraulic clamp and electric extruder drive. A couple of all-electrics have been sold domestically, but Taylor and Massimo Davoli, Milacron’s global product manager for shuttle machines, have high hopes for the new M-Series introduced last month at K 2016. Says Davoli, “There are other efficiencies besides energy savings: repeatability and reliability, and no hydraulic oil—attractive for food and pharmaceutical bottles. There’s no waiting for hydraulic oil to warm up after startup, so the machine gets on a stable cycle faster.” Milacron also introduced its first all-electric injection-blow machine in 2007, and a newer version at K 2013. A few have been sold

in Europe, and the first U.S.-bound machine is “on the way,” Taylor says. “Energy savings are less important for all-electric injection- blow,” he notes. The real driver is for pharmaceutical and cleanroom applications.” Milacron is extending its range of electric models. All sizes are now available as hybrids and soon as all-electrics. Very few fully hydraulic injection-blow machines are sold today, Taylor says.

CURRIER’S EXPERIENCE

Currier Plastics is a privately held, $35 million custom molder in upstate New York. It started as an injection molder, but now earns more revenue from blow molding, and most of its injection business is caps and closures for bottles. The firm has 25 injection machines, 13 extrusion blow shuttles—including the one Kautex electric machine, and 8 injection stretch-blow units (see Nov. ’14 feature).

Currier is putting its all-electric shuttle to a use that’s fairly unusual for these machines—1-oz HDPE hotel amenity bottles. “These machines usually have been used for larger components,” says Dustin Dreese, blow molding plant manager. “We’re doing smaller parts on a faster cycle, really working the machine. That produced some initial hiccups with component wear on the carriage drives, but Kautex has been very supportive from both their U.S. and German offices and solved all our issues.”

Because Currier has run the same bottles on hydraulic machines, it can make direct comparisons of machine performance. With the electric machine, says Dreese, “We’ve seen incredible consistency in clamp positioning and carriage movement versus hydraulics. That translates into less flash and fewer defects and less downtime to adjust the machine over a shift, day, or week.” He notes that his technicians have such rare occasions to adjust the machines that they have to refresh their familiarity with the controls each time.

Adds Steve Crawford, “The electric machine generates less than 0.5% rejects, vs. 0.5-1% on hydraulic presses. Greater consistency allows running higher cavitation. Currier’s KBB-60D double-sided press runs 12 parisons and 24 mold cavities. That compares with six or 12 cavities on hydraulic machines.”

“Consistent performance and the oil-free cleanliness of the electric machine present commercial opportunities for Currier,” notes Ron Ringleben, v.p. of business development. “It helps us expand our market share of food, beverage, medical, and health and beauty. We’re moving in new directions.”

John Ciampi also praises the ease of maintenance of the electric machine. “Because less labor is required for rebuilding hydraulic cylinders and seals, monitoring filters, and changing oil, about all we have to do now is clean the molds periodically.”

Currier expects its energy savings to improve as it adds more all-electric machines to both the blow molding and injection molding departments. Ciampi says, “It would be hard for us to justify purchasing this machine on energy cost savings, though being more sustainable is one of our company’s focuses. The real savings will come from reduced maintenance downtime and making higher- quality parts because of better machine accuracy.”

SPEAKING FROM EXPERIENCE

The Durban, South Africa, plant of Polyoak Packaging has operated four all-electric shuttle machines for as long as four years. They are all double-sided Uniloy UMS models of 14, 23, and 26 tons with two or six parisons. The molder also runs five hydraulic shuttles between 10 and 20 years old.

Polyoak Packaging is the largest rigid packaging producer in South Africa. It has eight divisions and 32 manufacturing plants with more than 2000 employees involved in blow molding, injection molding, and thermoforming of bottles, drums, tubs, buckets, and clothes hangers. The Durban plant has operations for two Polyoak divisions: Blowpack, which makes bottles and drums for agricultural and other chemicals, bulk beverages, detergents, kitchen cleaners, and home-repair products; and Lubripack, which blows motor-oil bottles.

The Durban plant has purchased only all-electric machines since 2012. Rhyan Matthews, operations manager at Durban for both divisions, still regards them as “relatively new,” but he is quite satisfied with their performance. Another Uniloy all-electric press is on order, and he says the plant will probably stick with all-electrics in the future.

Matthews considers it difficult to compare newer all-electric with older hydraulic machines, but two advantages are undeniable: “The electric machines are silent, while hydraulics are quite noisy,” he says. “And all-electrics are better in terms of housekeeping. We produce food containers and must meet ISO 22000 standards for food-safety management.

“Operating all-electric presses is very easy,” Matthews adds. “We can control everything from the control panel. We don’t have to check on the hydraulic pack. Maintenance is simpler—it’s just electric motors. No specialized hydraulic maintenance skills are needed. Hydraulic machines have more wear parts and require more labor to maintain.

“Troubleshooting is also easier with all-electrics. If a motor fails, you know it. But if a hydraulic valve goes, it tends to deteriorate gradually and you may not recognize it.”

Energy is expensive in South Africa, so increased energy efficiency matters, but Matthews has not quantified the difference between electric and hydraulic machines at this point.

Matthews praises the electric machines for being “very consistent. Once you set the clamp force, they hit it every time, on the dot. Our hydraulic machines take more finesse and more adjustments.”

He notes that quality issues related to the extrusion head itself are the same for both types of presses. “Die lines, shark skin, and head cleaning don’t change from hydraulic to electric.”

He also notes that the differences in clamp mechanisms have consequences for setup time after mold changes. With a hydraulic clamp, he explains, you set the mold height and the mold halves meet at the same spot. Clamp force is applied via hydraulic pressure. But on an electric press, clamp pressure is determined by position. That is, force is applied by one mold half pushing harder against the other, which moves the mold centerline slighty.

“Now, if you change mold height, the mold halves don’t meet at the same position, so you have to adjust the blow-pin position.” His machines don’t have automatic blow-pin adjustment. This adds to setup time. Matthews foresees a similar issue when changing clamp tonnage—moving the mold centerline slightly—though this has not come up yet in his plant.

Matthews has one solution in mind: “We need to standardize our mold height, It has to be very precise, within 0.01 mm.”

Related Content

Plastic Compounding Market to Outpace Metal & Alloy Market Growth

Study shows the plastic compounding process is being used to boost electrical properties and UV resistance while custom compounding is increasingly being used to achieve high-performance in plastic-based goods.

Read MoreMolder Repairs Platen Holes with Threaded Inserts

Automotive molder ITW Deltar Fasteners found new life for the battered bolt holes on its machine platens with a solution that’s designed to last.

Read MoreDesign Optimization Software Finds Weight-Saving Solutions Outside the Traditional Realm

Resin supplier Celanese turned to startup Rafinex and its Möbius software to optimize the design for an engine bracket, ultimately reducing weight by 25% while maintaining mechanical performance and function.

Read MorePEEK for Monolayer E-Motor Magnet Wire Insulation

Solvay’s KetaSpire KT-857 PEEK extrusion compound eliminates adhesion and sustainability constraints of conventional PEEK or enamel insulation processes.

Read MoreRead Next

Lead the Conversation, Change the Conversation

Coverage of single-use plastics can be both misleading and demoralizing. Here are 10 tips for changing the perception of the plastics industry at your company and in your community.

Read MoreBeyond Prototypes: 8 Ways the Plastics Industry Is Using 3D Printing

Plastics processors are finding applications for 3D printing around the plant and across the supply chain. Here are 8 examples to look for at NPE2024.

Read MoreSee Recyclers Close the Loop on Trade Show Production Scrap at NPE2024

A collaboration between show organizer PLASTICS, recycler CPR and size reduction experts WEIMA and Conair recovered and recycled all production scrap at NPE2024.

Read More